Double Tonguing For Fun and Profit

part one of a new series aimed at technical concerns of trombone players

In my previous posts, I presented various ruminations on music-related topics, aimed partly at musicians and partly at an audience with a little musical training. With this post I’m launching a series that is more specifically aimed at trombone players. I’m going to return to this series periodically. When this series is completed it will form a manifesto of sorts, not quite book, not quite technical study, and longer than an essay. I hope to dispel some myths floating around the trombone world and share a technique that I think can help people take their playing to greater heights.

The trombone is a simple instrument. It has one moving part. You can see the entire mechanism. However anyone who has watched a trombone player for a few moments realizes that the slide only controls so much. The really fun stuff happens hidden away from the audience, inside the mouthpiece, and even more strangely, inside the oral cavity, in a sort of saliva-filled chamber of secrets. Unlike most instruments, which can start a new note with a bow stroke, a pluck, a push of a key or a valve, the trombone does not usually start a note by moving the slide. A trombone player must use articulation, more so than almost any other wind instrument. During a performance, a trombone player’s mouth hosts a complex, unseen ballet with considerable muscular gymnastics, starring the prima ballerina, the tongue.

As I will detail in this series, there are many ways to rapidly articulate on the trombone, but there are two main ways, double tonguing and doodle tonguing. I’m a double tonguing jazz trombone player. Not doodle. I made the decision to develop a technique based on double back when I was 15 and never looked back. This is a flexible, useful technique that should find wider adoption among players in a variety of styles.

Unreleased track from “Assembly” (rec 2021), Jacob Sacks - piano, quarter=~160

When I started to get serious about jazz trombone, I realized I needed to develop a strategy to play fast. I like the idea of a “strategy” rather than just a “technique” because most people use a variety of techniques and ideas to express themselves at fast tempos, including choosing to not play fast at all.

MYTH: EVERYONE HAS TO PLAY FAST TO MAKE GOOD MUSIC

Why is it important to play fast? Well, it’s not. There is plenty of music, even brilliant, world-shattering music, that is not fast. I love Brian Eno, Morton Feldman, Portishead, and John Luther Adams. Brass players like Willie Ruff, Stuart Dempster, Andy Clausen, and Kalia Vandever have made lovely recordings of ethereal, slow paced playing that is missing nothing.

However, I’m also a fan of Mendelssohn’s Octet, Bach’s Goldberg Variations, Rafael Mendez, and Miles and Trane playing Two Bass Hit. Playing fast can be thrilling. It is a tool in the box that, if done well, can create excitement. It is no more essential, nor is it disposable, as a Major Seventh chord, or a repeated phrase, or vibrato. Just another element.

MYTH: PLAYING FAST IS SHOWING OFF

I want to make music with fast stuff in it because I like music that has fast stuff in it. Some people, especially trombone players, confronted with the challenges of their instrument, have responded by saying something like, “I just like to play lovely medium tempo melodies, so I don’t have to play fast.” Others have implied that fast playing is showing off. But in the professional world you are often asked to play fast passages, or to improvise in fast settings, whether you like doing them or not. If you truly want to make music that is only slow to medium tempoed, more power to you, but do not make this decision solely because the alternative is a daunting technical challenge. Be in control of your instrument. That means having a fast strategy.

I use the term “strategy” as a means to describe what a musician does with velocity, rather than simply “choose single, double tongue or doodle tongue”. Strategy can encompass many things. It can be an articulation or a group of articulations. On the trombone, it can be using alternate positions, lip slurs, or glissandos. It can be more philosophical than technical - perhaps it means avoiding long streams of notes and concentrating on short bursts of notes, or on repeating single notes, as a means to build excitement. There is no one proven strategy, and people are always coming up with new ones.

It seemed to me, as a jazz-obsessed San Francisco teenager in the 90s, that much of the jazz trombone world was doing doodle tonguing. I was turned off by this approach. Even the name of the technique I found to be unpleasant. It reminded me of uncool Ned Flanders from the Simpsons, saying “hi-diddley-ho, neighborino!” I was interested in serious 60s jazz, heady stuff like Coltrane, Joe Henderson, Wayne Shorter, Woody Shaw, and I was turned off by the music I associated with doodle tonguing. This, I thought, was Carl Fontana and his descendants, music that had a sort of “gee-whiz” small town earnestness that made me shudder in distaste. Fontana quoted Pop Goes the Weasel, played with the horn right on the microphone, phrased on the beat, didn’t seem to have any interest in Ornette Coleman or Miles Davis, and repeated pet phrases particular to the trombone, seemingly staying in the same handful of keys no matter what the chord sequence. I hated this. I was an urban teenage snob.

The type of trombone playing I was interested in was exemplified by J.J. Johnson, who played with a more even sound, a more even time feel, although not completely even. To my ears he was unmarred by the sound quality change of the second doodle syllable. I also loved his vocabulary. At that time there was some mystery about what articulation J.J. was using, but I heard the lightning fast, crisp, even runs from “Misterioso”, “Turnpike” and “Laura” and assumed he was double tonguing. He never published a method book. I had the sense that he subscribed to the philosophy, common with players of a certain generation, that you shouldn’t give away your secrets.

Much later I was to learn that, in an interview later in his career, he was asked about his tonguing and he said

It would be a combination of the doodle…certainly not tu-ka tu-ka [double] because I don’t do that well and it doesn’t seem to lend itself to jazz playing, jazz phrasing, for me at least. I’ve heard some guys that have had better luck than I.

The interviewer Tom Everett apparently made the same assumption I did and responded to J.J.,

I’m surprised to hear you say you’re using a doodle because there’s more clarity and at times separation, at least in your playing, than with the other people I associate with a doodle

To which J.J. replied:

A lot of it is just single tongue…and it comes from just practice practice practice.

In his two part answer, he shows his strategy is a more complex combination of things than just a technical choice. Paradoxically, while he was an unparalleled virtuoso who could play at blazing speeds and play long strings of pristine bebop 8th notes, his fast solos usually deployed these passages in moderation. While the trombone world obsessed over his technique, in interviews again and again (“I am not at all preoccupied with speed.”) he rejected the idea that he was a speed demon. A fast J.J. solo often consisted of highly rhythmic and melodic material with only a few longer 8th note lines. He liked to play repetitions of single notes, both as triplets and as 8ths. Compare this approach to, say, Sonny Stitt, where the bulk of a fast solo would be long 8th note lines. Our greatest exponent of the 8th note line was also very judicious.

When I was studying JJ, I was also interested in one of the foremost virtuosos of the trombone, Christian Lindberg. His recording of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons on the alto trombone showed me that double tonguing could be spectacularly precise. I played in the San Francisco Youth Symphony. Trombone section members needed to double tongue to play the standard orchestral repertoire. Why would I put considerable effort into doodle tonguing, shunned in the classical brass world, when I needed to master double anyway?

As I grew out of my teenage snob years (and entered my adult snob years?) I came to realize that doodle-tonguing was merely a tool, not a stylistic marker. Although it is associated with jazz, it has a long history, including mentions in recorder method books from the 16th century. Doodle-tongue could be used to play Fontana-style swing, or it could be used to play avant-garde jazz. Like double-tonguing and single tonguing, it has inherent strengths and weaknesses.

From years of practicing and playing with doodle tonguer Ben Gerstein I learned that doodle could be shaped to play transcriptions of Nancarrow, Boulez or late Coltrane.

Furthermore, the more I studied and met other trombone players, the more I learned that this dichotomy, one technique or the other, was a simplification of the actual strategies that players used. I took a lesson with Steve Davis and learned that he moved the tip of his tongue forwards and backwards across the top of his mouth, a sort of “da-der-da-der” tongue. Marshall Gilkes does the same. Dave Taylor single tongues, but can do it very quickly. Elliot Mason single tongues in conjunction with glissing and lip slurs. Ed Neumeister does single tongue and a sort of “ta-la-ta-la” tongue but only below high A, and otherwise double tongues.

Last year I posed a question to facebook, in a thoroughly unscientific poll: “trombone players, who single tongues, who double tongues and who doodle tongues?” I got hundreds of responses from players in my social media circle, many of them NYC jazz professionals. Predictably, most had nuanced answers, detailing their strategies, including those who rejected the limited premise of the question. Some typical (and well-expressed) responses

I just single tongue. Never got the other styles up to snuff for practical application. I’m in the camp of internalizing the sound in my brain to the point that the anatomy falls into place.

I do all of the above depending on what I need at the moment. Certainly the practice of using against the grain motion as articulation, which you practice when you doodle, is something that comes in very handy.

Different techniques for different ends, but I will say that for me doodle is the most versatile , because I can soften it up or make it sound nearly as percussive as double tonguing. On another note, I asked the late great Alan Raph “how can I speed up my single tongue?”. He responded dryly: “slow down your multiple tongue”.

MYTH: DOUBLE IS FOR CLASSICAL, DOODLE IS FOR JAZZ

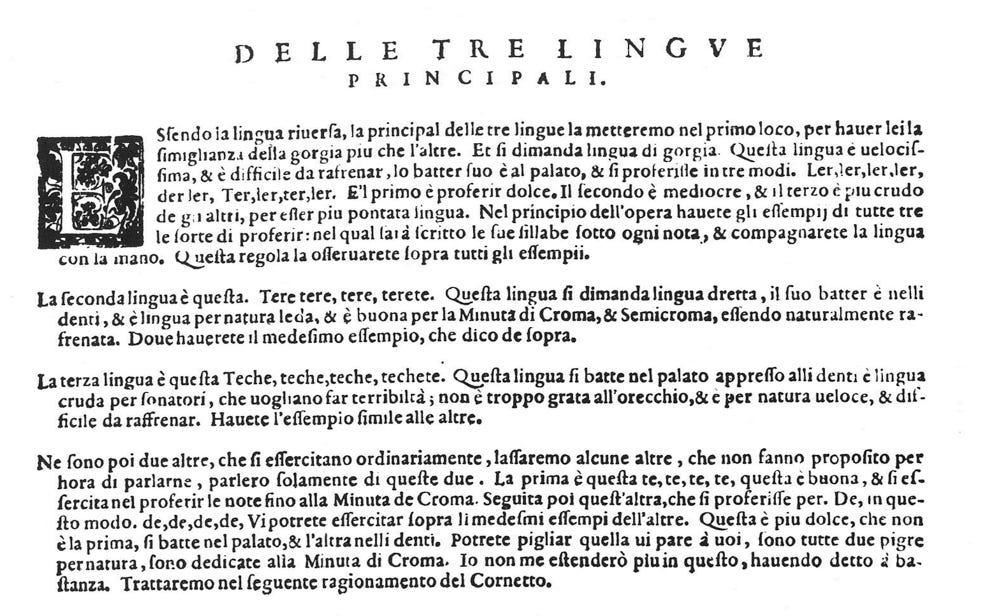

Even in 1584, Italian composer Girolamo Dalla Casa detailed multiple approaches to articulation in his treatise “Il vero modo di diminuir, con tutte le sorti stromenti. Di fiato, & corda, & di voce humana“ (“THE TRUE WAY OF MAKING DIMINUTIONS ON EVERY SORT OF INSTRUMENT: WIND, STRING, AND VOCAL”). Keeping in mind the Italian pronunciations of the “r” and “che” sounds, the syllables he describes as “Ler, ler, ler, ler, derler; Ter, ler, terler”, “tere tere, tere, terete” and “Teche, teche, teche, techete” correlate to doodle, da-der (like Steve Davis), and double tonguing. His method book was aimed at recorder and cornett players. (Recorder players still use these, and refer to doodle as “didd-le” or simply as another type of double tongue. ) My assumption about doodle being recent or being exclusively a jazz technique was wrong.

Meanwhile, not knowing any of this, I continued my practice. I adapted Arbans, worked on easier bebop tunes, learned J J solos, Curtis Fuller solos, before tackling trumpet, saxophone and piano solos, the typical type of study that is essential to jazz instrumentalists. My double tonguing, initially rigid and harsh, became more flexible and smooth. I integrated it into my playing in a way that I think is successful.

“Acid Metacognition” from Matt Pavolka’s Horns Band (rec 2013), Matt Pavolka, bass, Mark Ferber, drums, quarter=~280

I am not a speed demon. Trying to play the ridiculous tempos of, say, 50s Sonny Rollins/Max Roach is still a daunting challenge, and my strategy for that is going to include very few strings of 8th notes. There is certainly music to be made at that speed, 400 bpm or more, although sometimes it is more of a thought experiment than a satisfying work of art. Perhaps students who wish to live (dangerously!) at those tempos would be best served by an example other than mine. But at ~220-320bpm, when single tonguing begins to be inadequate, and there is still excitement and music to be made without veering into the frantic zone, my approach to double tonguing can be very helpful. It is my hope that, using this technique, trombone players become more comfortable with those tempos, perhaps even eliminating some of the notorious distance between the capabilities of the instrument compared to our more nimble and verbose instrumental cousins.

In this series of posts I will attempt to detail my technique, along with an in-depth justification for why I chose it. I’m going to talk a lot about trombone articulation, but not exclusively trombone stuff. Because trombone articulation is so related to rhythm, I’ll discuss jazz swing feel. I’ll touch on musical philosophy, instrumental comparisons, famous fast tempos in jazz, multiple tonguing around the world, anatomy, phonetics, diction, jazz history, Ron Carter, Hariprasad Chaurasia, Fanfare Ciocarlia, Clifford Brown, and Milt Jackson.

I will often refer to “8th” notes as a generic term but obviously in some musics these techniques will more accurately apply to 16ths or 32nds.

I will be talking a lot about jazz, which I love and partake in, but not exclusively about jazz. In my career I use double tonguing for non-idiomatic experimental music, balkan music, rock, funk, mexican, afro-cuban, music inspired by Hindustani, Carnatic and Qawwali traditions - if you are interested in these things and not into swinging jazz, fine with me. Just take this info and do with it what you will.

“Digression on the History of Jews and Black Music” from “The Heavens”, me on trombones/baritone/tubas (rec 2011) quarter=~170

Next in the series:

Double vs Doodle: The Ultimate Smackdown

So glad you mentioned this on the 'Trombone Chat' forum, as I wasn't aware you were doing a Substack thing. Great!

A currently relevant topic to me (well, more like 30 year topic!) because I, like you, has never really been turned on by the 'super-doodle-tongue' music being played by the 'super-doodlers'.

A lot of that most likely due to my being involved with all kinds of music and never actually having the time practice 'doodle-tonguing' very much... and basically finding that the 'conventional' methods of how it was/is being taught very hard for me perhaps due to having pretty crooked teeth or playing for too long on a mouthpiece rim that was much too small for my facial makeup.

I really appreciate your musical outlook, hearing your playing, and am looking forward to more of your 'manifestos'!

Cam Millar