Envelope revolution

On September 15, 1957, 24-year-old Curtis Fuller stepped up to a mic at Van Gelder studios in Hackensack NJ. Standing next to him were Lee Morgan and John Coltrane. Much has been said about the harmonic, melodic, rhythmic innovations of these giants. But there is an unheralded focal point of this record: the gorgeous rectangle of sound, the meticulously rendered object, the study in breath control and stylistic elegance that is the shape of any single Curtis Fuller note. Attack, decay, sustain, and release, synthesized not by transistors but by a human body, to create a mid-century building block of acoustics.

A brass player begins a note with an “attack”, similar to the syllable “ta”. The player creates an air seal by touching the tongue to the top of the mouth, usually where the top teeth meet the palate. Lungs and diaphragm force air against this seal. In the instant of attack, the tongue releases the air and jumps down to the bottom of the mouth. The lips buzz to create a sound.

Following this, a note can take on many shapes. It can grow in volume immediately, grow gradually, or diminish quickly. The pitch could waver with vibrato, or remain still. Vibrato can be added to the end of the note, which itself has another series of variables. All of these things make up the “shape” of the note, or to use a term from electronic music, the “envelope”. An envelope can refer to changes in volume, timbre, or pitch.

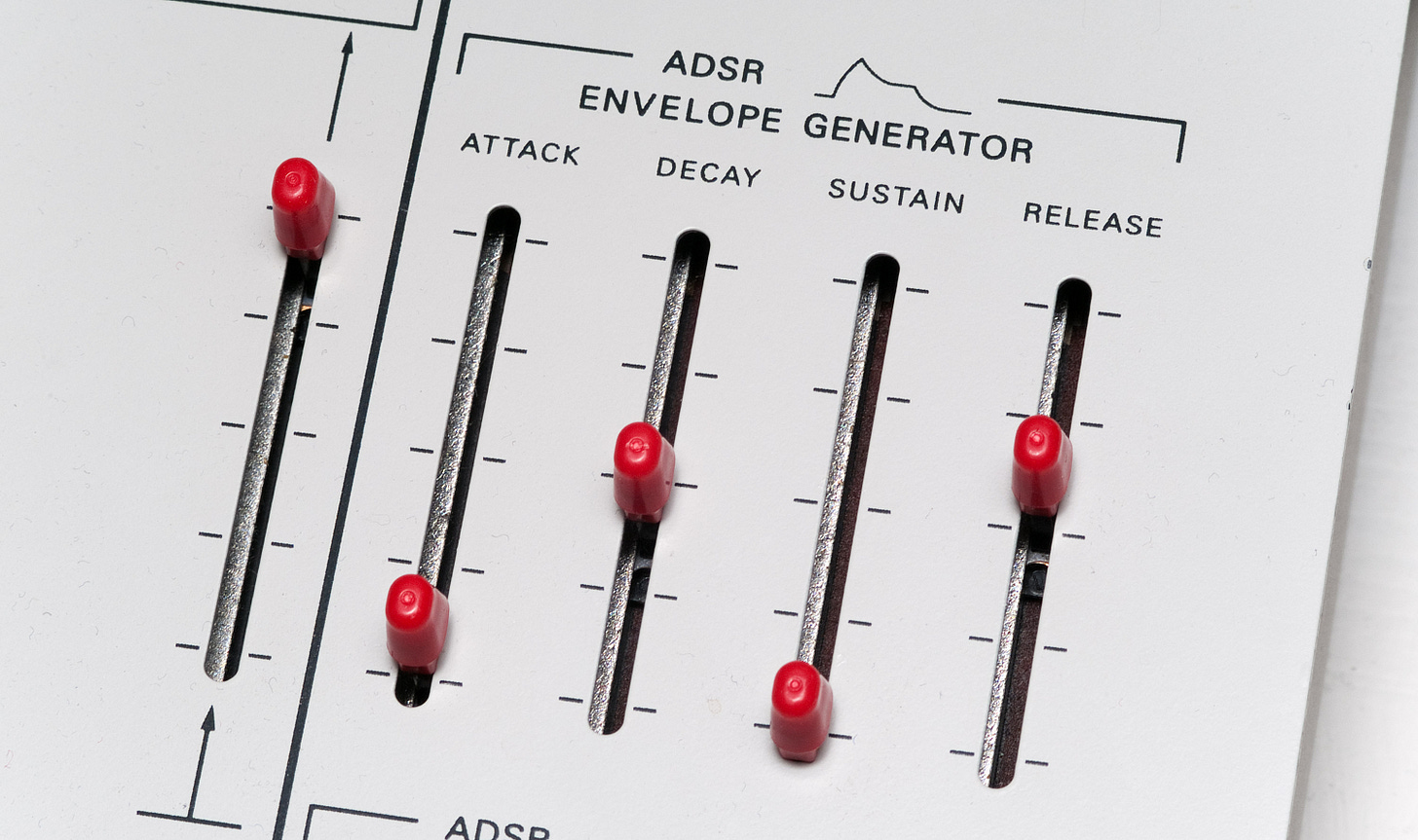

In the 60s, Robert Moog created an envelope generator for his new synthesizer that mimicked the stages of volume or brightness that an acoustic instrument underwent. He labelled these Attack, Decay, Sustain, Release, or ADSR; standard on synthesizers since. By adjusting these parameters a synthesizer player can imitate the envelope of a bell, a tuba, or something completely artificial. Moog’s tool gave numbers to the shape of notes; science applied to music.

Brass players from the first half of the 20th century have stylistic traits in their “envelopes” that have gone out of fashion.

Bohumir Kryl was a virtuoso whose playing had a singing quality. Notes begin with a clear attack, but quickly grow in volume and brightness, reaching peak fullness of sound after around ¼ of a second. The envelopes are wedge shaped rather than rectangular.

Louis Armstrong’s notes grow in volume and brightness after onset. Most of the longer notes have a rapid vibrato, deep in pitch.

For a player like Jack Teagarden, a note’s envelope resembled not so much a rectangle but an ornately shaped, hand-crafted object. The syllable sounds less like “Ta”, more like “Mwshwah”.

In a podcast by Barbara Haws, the archivist of the New York Philharmonic, speaking with Joe Alessi, principal trombone since 1985, Alessi remarks on the changes of brass playing in the mid century.

Upon hearing the 1944 recording of the NY Phil playing Tchaikovsky’s 6th with principal trombone Armand Ruta, Alessi says (about 37’20”):

It could have been slide vibrato. If I had used vibrato on this chorale I’d be fired. Very strange…I don’t think there’s any modern day interpretation like that. I’ve never heard it with that amount of vibrato

On the 1947 recording of Mahler 5 with William Vacchiano on trumpet ( 40’20”) :

Brass playing and styles have changed. That was the style back then. I hear the notes beginning large and then they decay, which is not a bad idea in general. It’s almost exaggerated.

Alessi specifically connects the shaping of the notes to the influence of operatic vocalists.

That was the style, maybe it comes from the opera background. A lot of musicians listened to a lot of opera. The connection between singing and brass playing I think was more connected than it is now.

On Ruta, Alessi connects the style to the necessity of Philharmonic musicians to be versed in jazz and dance music.

The philharmonic was only a 26 week season. They did a lot of other things, these musicians. They played in dance bands…A lot of them made most of their money outside of the orchestra.

In the mid 40s, the war ended, and bebop was born. Dizzy Gillespie and J.J. Johnson demonstrated harmonic complexity, breakneck tempos, and rhythmic mastery, but they also played with a clarity of attack, decay, sustain, and release that we have come to associate with modern brass playing. They presented acoustic envelopes for the atomic age.

Although Dizzy idolized Roy Eldridge, he dispensed with his vestiges of swing era note shapes and played with a straighter tone. In the 1944 recording of “Woody N You”, the first recording of bebop, Gillespie’s clarity and light vibrato contrasts with leader Coleman Hawkins gruff attacks and heavy vibrato.

J. J. seven years younger than Dizzy, said:

I learned a lot just by asking Dizzy questions about brass playing and about the technique of jazz playing and what not.

His favorite trombonist was Fred Beckett, because as J.J. said, he was

the first trombonist I ever heard play in a manner other than the usual sliding, slurring, lip trilling or 'gut bucket' style.

In an interview with David Baker, J.J. emphasized his interest in tone color:

I’m still preoccupied with trying to be articulate and clear and to approach jazz improvisation with logic. I am not at all preoccupied with speed. I am preoccupied with timbre.

In his 1947 recording of Yesterdays, each note starts with a clear attack and stays at full volume. His lip vibrato is shallow in pitch and steady in tempo. Very few notes have glisses.

Comparing the playing of 1940s Dizzy, and J.J., along with Miles Davis (briefly Vacchiano’s student!) and Fats Navarro, to the classical players of the era is elucidating. Could it be that the jazz players actually preceded their classical counterparts in the revolution of clarity of envelope? Certainly J.J.’s perfection of tone has long had the respect of many in the classical world, including admirer Joe Alessi.

By 1958, on “J.J. in Person”, vibrato was almost nonexistent. On “Laura”, he presents straight-toned note shapes, only coloring longer notes with a slight lip vibrato at their end, a single lowering and raising of the jaw. This “terminal vibrato”, vibrato that appears towards the end of the note, was popular in players from the swing era. J.J.’s idol was Lester Young, who used a lighter, straighter tone than most of the other swing saxophonists, and terminal vibrato. His influence is unmistakable in the new era of clarity.

Curtis Fuller, 8 years J.J.’s junior, adopts the straight tone with terminal vibrato as a basis of his technique. On his Blue Train solo his sound is as smooth as the roofline of a Neutra house. The terminal vibrato is a way to keep one foot rooted in the past, as a mid century house might have stylized molding, echoing the form of a previous era.

Grachan Moncur III, a few years younger than Curtis and 13 years younger than J.J, would take the modernist approach to an even greater extreme. He started out as a J.J.-influenced bop player. On records like 1962’s “Jazztet” he has an approach similar to his predecessors - straight tone, terminal vibrato on longer notes.

The next year he proved to be a stunning, visionary composer who was more willing than either of his predecessors to dive into the avant-garde. In his solo on the title track of “Evolution” (recorded in 1963), over a dissonant backdrop, in what is perhaps the most minimalist composition in jazz to date, he presents a completely un-ornamented tone which dispenses with terminal vibrato altogether, a stylistic step that J.J. and Curtis never took. He uses slight glissandos at the end of phrases, but they sound less like swing era mannerisms and more like an exploration of microtones.

This was the apex of stylistic plainness. The pendulum was soon to swing the other way.

The late 60s brought the psychedelic era. Maximalism was back. Haight Ashbury Victorian interiors were once again covered in bric a brac.

Roswell Rudd, about the same age as Grachan Moncur, resurrected older, swing era articulations and brought back the broader tonal palette of the dixieland players. The 70s would see the rise of Ray Anderson and George Lewis, who were willing to sacrifice clarity of tone for maximum expressive impact.

There was no swing of the pendulum in the classical world. Arnold Jacobs, tuba player of the Chicago Symphony, starting around 1960, deployed scientific methods and surplus Navy Diving equipment to the study of breathing and tone. His foundation sells a device with a ping pong ball in a plastic tube. You blow through the tube to keep the ping pong ball afloat. The ball is the physical representation of ADSR.

Brass teachers began to talk less about copying opera and more about blocks of sound. Among others promoting this new, precise style is Alessi.

Upon hearing a 1980 recording of the NY Phil with Phil Smith on Mahler 5, Alessi remarks

His decays are different, his decays last a long time, whereas Vacchiano would decay almost immediately

The effect of envelope style is as important an element to one’s sound as whether or not you choose to emulate Woody Shaw’s harmonic sense. The study of note shapes/attacks/envelopes/vibrato is perhaps less exciting than learning “killing” licks or upper structure harmonies. Youtube channels aren’t dedicated to in-depth terminal vibrato analysis. Yet it is essential to style. After all, the first thing you hear from any player, before melody, harmony, or rhythm, is the envelope. The choices made by the mid-century musicians put them in the forefront of a greater artistic movement that shunned ornamentation. Listeners who heard the opening of Blue Train would immediately have a sense that it sounded “modern”, that it was of the age, different than what had come before.

Yeah Jacob! Passionate erudition grounded in experience. Looking forward to more!

Great read! Thanks. Initially when I read your subtitle I thought that the article was going to be about the E natural Curtis Fuller plays on the 6th measure of his first chorus on “Blue Train”…that’s a pretty powerful note:)