This post is part of a series largely geared towards trombone players. I’m also going to touch on a lot of tangentially related musical goodies.

If you are trombone-articulation curious, read on. Otherwise, sit tight, I’ll have plenty of non-trombone specific content in the weeks to come. No apologies for going so deep into a niche topic. My whole career could be described as going deep into a niche topic.

In my first post about double tonguing I explored why exactly someone would want to play fast on the trombone. In this post I will compare the two major approaches to rapid trombone articulation.

My technique of choice is double tonguing, but I don’t wish this to be a takedown of doodle tonguing. After all, if doodle was good enough for J J Johnson, it is good enough for anyone. Rather, I wish to dispassionately, and in great detail, explore the differences between the techniques with the hope that more insight into their nuances will result. Study leads to understanding which leads to mastery.

In many ways this match-up resembles classic rivalries. Yankees vs Dodgers, States rights vs Federalism, French bow vs German bow, jazz guitarists who pick every note vs those who prefer legato, matched grip vs traditional grip. In instrumental technique there are often opposing schools, technical choices that lead to stylistic camps. This is somewhat true with doodle/double, although the styles are not strictly delineated.

What is double tonguing?

Double tonguing is a paired articulation. A player’s tongue alternates between two types of attack. In the first type the tip of the tongue creates a seal by touching the teeth, blocking air from passing through the mouth until the moment it moves back. Linguists call this syllable a “plosive” or a “stop” - it stops air.

The second syllable, “kah”, is also a plosive, but stops the air using the middle or body of the tongue to create a seal against the roof of the mouth.

Linguists make distinctions between “voiced” and “unvoiced” syllables in speech, to indicate whether or not the sound uses the vocal chords. But playing a brass instrument, we do not purposely use our vocal chords while playing unless growling or playing sung multiphonics.

In English, a “ta” syllable is voiceless and a “da” syllable is voiced. But in brass playing, the distinction is different. Both are voiceless. With “ta” syllable, the tip of the tongue touches the teeth or the point where the teeth meet the palate, but with “da”, the tip of the tongue touches further back on the palate. In English, “ka” is voiceless and “ga” is voiced, but both use the middle or body of the tongue in the same place on the roof of the mouth. In brass playing, “ka” and “ga” both are voiceless and are indistinguishable. If you apply to work in a dairy farm, but have lost your voice, you will have a hard time whispering to your boss that you would like to “grate cheese” and not “crate cheese”. I’m leaving now; let me grab my goat.

What is doodle tonguing?

Doodle tonguing is also a paired articulation. The first syllable can be either “ta” or “da” as detailed in double tonguing description. For the second syllable, the tip remains positioned at the teeth or top of mouth, creating a restriction of airflow, while sides of the tongue move towards the center to allow airflow to pass. Linguists call this a “lateral release”.

In American English, which has a variety of accents, most speakers would pronounce the word “doodle” with a lateral release on the second syllable. But the great variation in accents in English from other countries, not to mention phonetics from other languages, means that some people will require lots of training and explanation to even say the word doodle as it applies to trombone playing. “Bottle” as spoken by Cockney Michael Caine will sound like “boh-oh”. Spoken with a French accent a la Inspector Clouseau it might be “boh-till”. A similar problem exists for tu-ku and double tonguing. Some languages don’t even have a voiced dental plosive (tah sound). The tongue must be trained.

Common wisdom is that doodle is uneven. Why is this? I don’t actually understand exactly why. My theory is that the position of the tongue on the “ul” syllable takes a fraction of a second to reach, and for most people this is slightly longer than the time it takes for the tongue to reset to “du”. But it can’t take too much time; after all, people can doodle tongue quite quickly once they get the hang of it.

Perhaps this is Anglo linguistic bias. Because in English we pronounce words like bottle, doodle, coddle, or mottle with an accent on the first syllable, the timing of the second syllable is naturally a little delayed. If jazz musicians spoke a language where the words were pronounced bot-TLE, cod-DLE we would end up with an articulation that naturally produces a sort of reverse swing.

Similarly, we speak of double tonguing as being inherently even, but someone speaking another language, like one where a ta is often clipped and attached to a ka sound (t’kah d’gah etc ) might have a different inclination. To see the correlation between pronunciation, accents and rhythmic feel one need only listen to some Brazilian music with the distinctive 8th note feel that is the result of Portuguese pronunciation.

MYTH: DOODLE IS BETTER SUITED FOR JAZZ BECAUSE IT SWINGS

Conrad Herwig, writing for online trombone journal, says:

If you're playing classical music or get called for a studio date, you have to have double tonguing in your arsenal. But it's kind of stiff and doesn't lend itself to jazz. You hear guys who might be playing pretty smooth, but then they go into double-time and it isn't in context. Doodling allows your double-time ideas to flow smoothly and naturally out of your single-time ideas. And it really does lend itself to swinging.

In Bob McChesney’s “Doodle Studies” book, he writes:

In addition to its speed, smoothness, evenness and precise timing, doodle tonguing lends itself perfectly to music played with a swing feel. Even when rhythmic patterns may be slow enough to single tongue, doodle tonguing can often be preferable because it easily produces swing.

These statements assume that swing eighth notes should always be uneven. In fact, there are many players that have relatively even swing 8th notes. There are a wide variety of approaches to swing 8th note feel, one of the factors that defines a player’s style. There are players that have consistently even 8ths, or very swingy 8ths, or a combination of both, even within a single phrase.

In the 60s, especially with the influence of Miles Davis’s rhythm section with Tony Williams, 8th note feels tended to straighten out.

Teo’s Bag (rec 1968)

There are no hard and fast rules about the relationship between content and 8th note feel - there are swing era players who have, at times, a more even feel, like Django Reinhardt, and more modern players who may have a very swingy feel, like Joe Henderson. Describing the rhythmic language of these players as one thing or another is a simplification. You will find a variety of feels within a single solo.

At very fast tempos, all swing feels tend to become more even. We still perceive the best of them as “swinging” but often this is a result of other factors, such as unpredictable accents or overlaid polyrhythms.

Milt Jackson is often more even, but not exclusively so.

On the Scene (1952)

Dexter Gordon, known for even 8ths, but often intersperses more swingy passages.

It’s You or No One (1961)

While it is true that beginners learning doodle tonguing will find it inherently suited to rudimentary swing playing, they will eventually have to master it enough that they will be able to even out the 8th note feel if they want to. Similarly, double tonguing, inherently square, must be trained to be uneven or more swingy. If Australians can say “G’day”, the ga can be as close to the da as the ul is to the da. The player just has to get used to saying g’dah g’dah g’dah. Neither of these processes are insurmountable.

The swingy nature of doodle tonguing is such a strong pull that some players incorporate it into their style. Curtis Fuller, for example, never straightened out his 8ths regardless of what the rhythm section was doing, and just swung on everything. Here he is on a funk feel from his album “Crankin” (1975). To me, this is not a shortcoming, but just part of the nature of his style.

J.J. Johnson sometimes played with more even 8ths or 16ths and sometimes played with a more swingy feel.

Misterioso (1958), combines even playing with more swingy playing

A major part of this discussion centers around swing 8th notes. But in many situations a player might want to use multiple tonguing for all kinds of other rhythmic playing. Apart from the necessity of playing more even 8th notes, a multiple tonguing technique must also facilitate even triplets, other tuplets, non metric fast notes, or groups of notes that slow down and speed up. For some situations double tonguing can be paired with triple tonguing to play odd groupings (TA-ka TA-ka-ta). In others, such as long unaccented triplet phrases that imply a faster tempo, the player may want to use double tonguing (instead of TA-ka-ta TA-ka-ta, use TA-ka-ta KA-ta-ka. )

In this example I’m playing Have You Met Miss Jones in a medium tempo 4/4, but overlaying triplet phrases to imply a fast tempo, as well as groups of notes that speed up from triplets to sixteenths. The ability to play fast notes evenly, if desired, is key here.

Jacob Garchik, Vinnie Sperrazza, Dave Ambrosio, Live at Ibeam (2011)

MYTH: DOODLE IS BETTER SUITED FOR JAZZ BECAUSE IT’S LEGATO

McChesney’s book:

The technique [doodle] also produces much smoother articulations than can be achieved with the standard multiple techniques of double and triple tonguing.

Frank Rosolino, Downbeat 1977:

You can't play jazz by double-tonguing. It comes out restricted, too staccato—duka-duka-duka-duka.

One assumption here is that doodle is more legato than double. But as I will demonstrate with this series of posts, double can be trained to be very legato.

Another assumption is that jazz 8th notes must be legato. While it is true that the majority of trumpet and saxophone soloists play legato 8th notes, it’s not universal. Clifford Brown articulated at medium up tempos, although because of the nature of the instrument, he wasn’t bound to an articulation like a trombone player. He could alternate doodle tongued, articulated passages with legato 8ths and legato triplets. Once again, combinations of more even and more swingy phrases.

“Daahoud” (1954)

There are instruments that obviously can swing but have no mechanism for legato, such as piano, drums, or vibraphone. In the Milt Jackson clip above do we come to the conclusion that the absence of legato means it doesn’t swing? Why does that assumption persist among trombone players?

Furthermore, on many instruments improvisers create rhythmic excitement by playing 8th notes on a single pitch. These can be full duration or short, accented or not, but they can not be “legato”, which refers to the transition between different pitches. So for these passages, doodle tongue, with its supposed superior legato capabilities, provides no benefit.

MYTH: DOUBLE TONGUING IS ONLY FOR CLASSICAL TROMBONE

As I detailed in my first post on tonguing, both double tonguing and doodle have a long history and wide variety of usage, including in classical music. Nowadays, doodle is still used by baroque recorder players, and some jazz trumpet players, and of course often used by jazz trombone players.

Double tongue is widely used by brass and wind players in classical music, and by some trombone players in jazz. It is also used in many diverse musics around the world. Mexican banda sousaphone players use it for showy flourishes where it is nicknamed “helicoptero”. It is used in techniques for playing Australian didgeridoo, Dominican merengue saxophone, Moldovan Eb clarinet, and Serbian-style tenor horn.

The North Indian bansuri player Hariprasad Chaurasia had an astonishing command of double tonguing.

from “The Mystical Flute of Hariprasad Chaurasia” (with Zakir Hussein, 1983)

Classical singers from India and from the Pakistani qawwali tradition, like Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, also use a form of double tonguing. Because they can freely use their lips, a singer has many more syllables available that a brass player cannot do, but still alternating dah or nah and gah is a crucial element of these styles.

Busta Rhymes guest turn in Chris Brown’s 2011 Look at Me Now originally featured a percussive but still narratively clear bragging verse with many phrases like “gotta get go gotta get it” https://genius.com/Chris-brown-look-at-me-now-lyrics

But when he revisited the song for a performance at the 2023 Grammy’s he changed the lyrics to become almost unintelligibly abstract, a virtuoso display of rapped double tonguing, alternating tah and gah syllables with no meaning.

A more pedestrian example is anyone saying “here kitty kitty kitty”. All this is to say, double tonguing has a very wide user base and broad applicability. If you are interested in playing any of these kinds of music or in exploring their sounds through the prism of the trombone (as I am), you would be well served by studying double tonguing.

MYTH: THE “KAH” SYLLABLE IS TOO WEAK TO START OR END A PHRASE

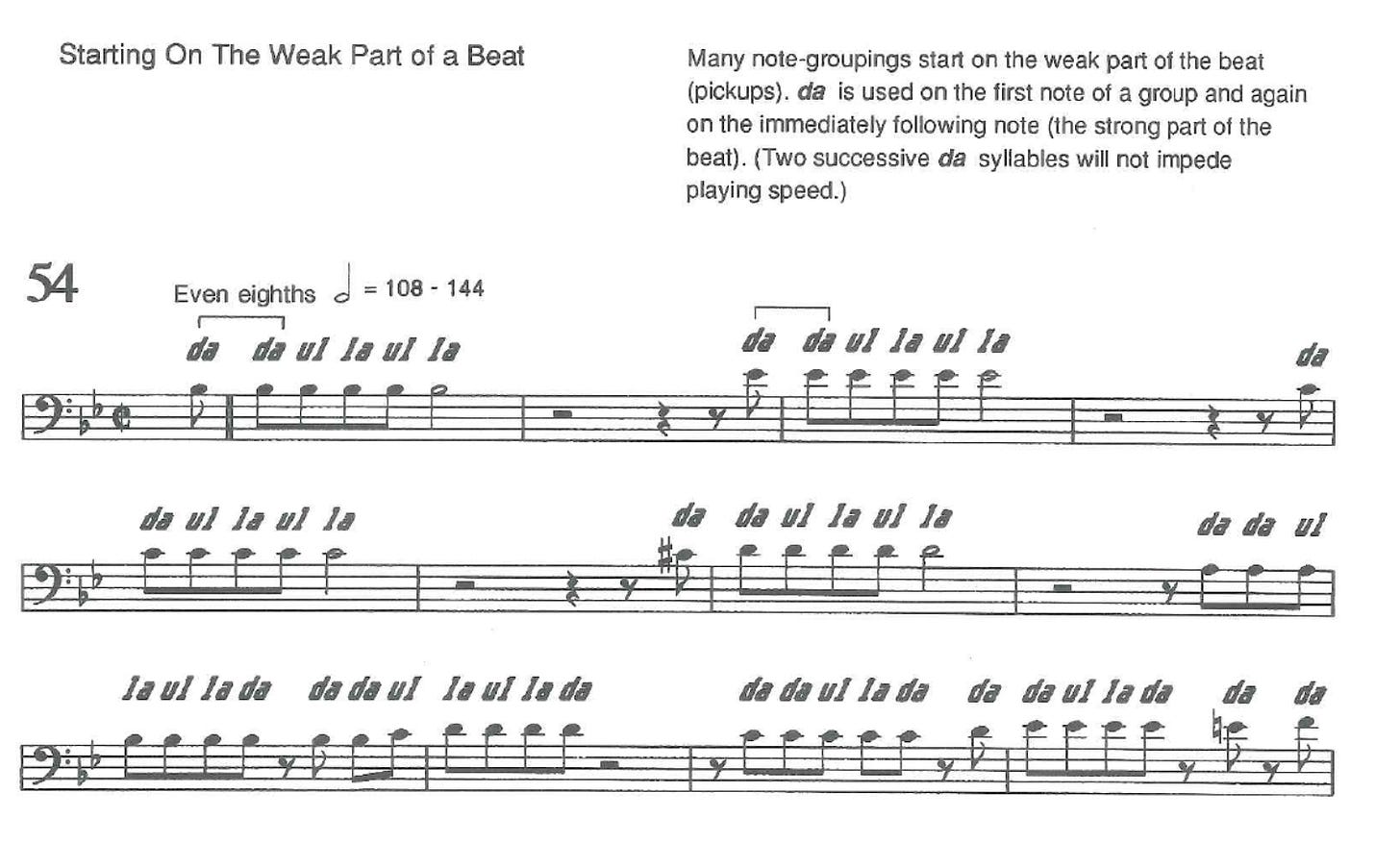

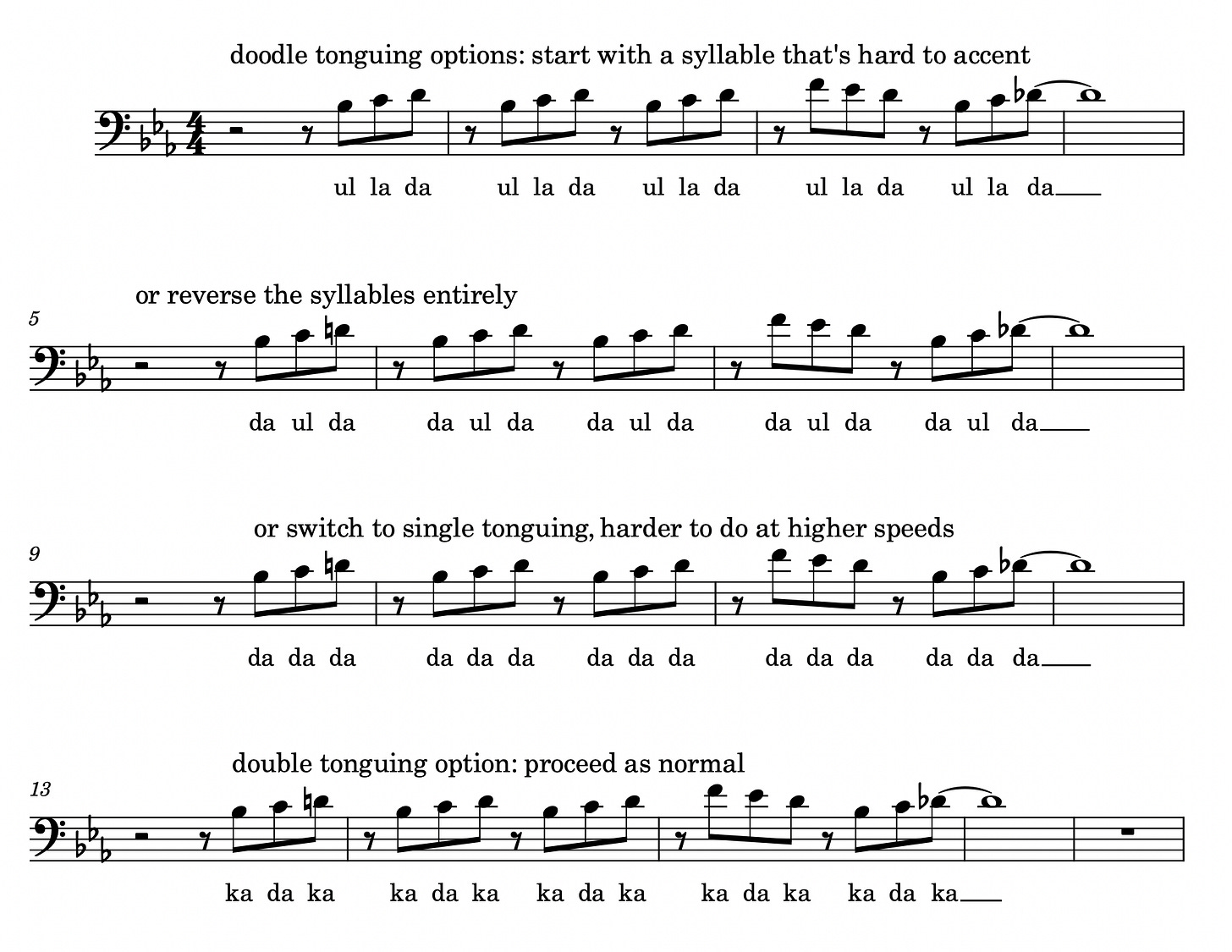

In doodle tonguing guides the instructor will tell the student that doodle tonguing in jazz is usually combined with single tonguing and natural slurs. This is especially important with bebop phrases that start on upbeats or end on upbeats. The reason is that the “ul” syllable does not lend itself to the type of upbeat accent that you typically find in bebop phrases. In addition, players avoid landing on long notes with an “ul” syllable. The position of the tongue on “ul” is awkward and does not lend itself to a full sound.

Some players denigrate doodle entirely, saying that the compromise of sound on the “ul” is unacceptable.

Steve Turre, speaking to Javier Nero for his 2017 dissertation “Developing and Implementing the Double and Triple Tongue Technique”, says

Generally speaking people that doodle tongue don't have a resonant sound, because the tongue blocks the air stream.

But I have found that, in phrases of all fast notes, skilled doodle players have minimized the negative quality of sound on most “ul” syllables, and this is not really an issue.

For a phrase that ends with an upbeat short note, or an upbeat long note, doodle players switch to single tonguing. Same for phrases that begin on an upbeat.

This is not necessary with double tonguing. The “kah” sound can be accented or adjusted for bebop phrasing and does not affect the quality of sound on a long note. Players might combine double tonguing with single tonguing but they don’t have to in this instance.

Consider the opening of the standard “Four”, often done medium tempo, but sometimes played faster:

This seemingly minor detail becomes magnified in studying the nitty gritty of bebop-type phrasing, which has a lot of passages that start or end on upbeats. Doodle tonguers must adjust syllables depending on context until adaptation is second nature. Double tonguers also have to adjust syllables, switch to single tonguing at times, or leave out tonguing to play with natural slurs. It’s a different set of modifications.

Next up: all about single tongue

+

double tonguing first steps

Thanks. I'm a guitar player so this is of limited practical use but it's always interesting to read about the techniques and ideas (trials and tribulations) other instruments face.

I’m very curious about baroque recorder players using doodle tongue, where did you hear about that?