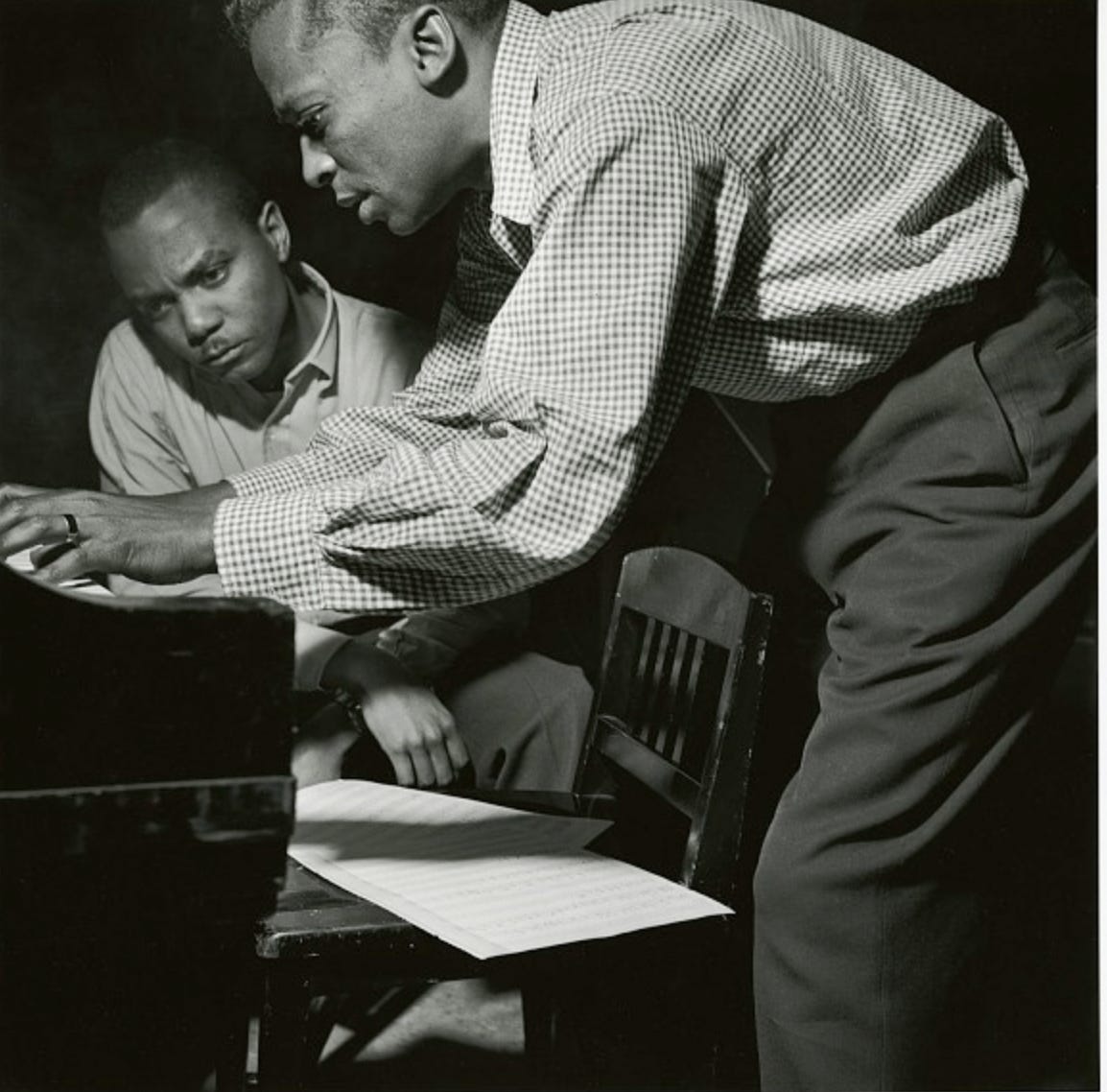

Miles and J. J.

a friendship and a confluence

In 2022 a pair of curious tracks from two of our greatest jazz musicians appeared on a Columbia 3 CD box set. Called “The Bootleg Series, Vol 7: That’s What Happened”, it compiled some live recordings from Miles Davis’s band in the 80s and various outtakes from Star People, Decoy, and You’re Under Arrest. But what caught my eye and blew my mind is two tracks from 1982 called “Minor Ninths, Part 1” and “Minor Ninths, Part 2” featuring the duo of J.J. Johnson on trombone and Miles Davis on electric piano.

Miles Davis on keyboard was a chord player, whether it was on piano with Sonny Rollins or on organ on Get Up With It. On these 80s tracks Miles plays vague distant harmonies. In “Part 2”, J. J. plays in a bluesy manner we are accustomed to. But Part 1 is really something else. This is one of the most abstract things J.J. ever recorded.

J.J. was also featured on a long blues solo on a slow funk beat called “Celestial Blues Part 3”.

Yes, in addition to 20-something sax hotshots Bill Evans, Bob Berg, Gary Thomas, Branford Marsalis, Rick Margitza and Kenny Garrett, Miles’s 80s band front-line briefly featured 58 yr old J. J. Johnson.

The fact that these oddities are with his old buddy of 35 years, Miles Davis, is important - their friendship and record of creative collaboration over decades is a fascinating record of mutual admiration.

Miles’s nephew Vincent Wilburn said:

Uncle Miles loved J.J. I remember J.J. coming out to the house in Malibu. Uncle Miles was tight with a few of the buddies from the past. When we were on the road, he’d love to see them. They’d come backstage and hang. And J.J. did that a lot.

Two men from the Midwest who came to NYC as kids in the 1940s to join the bebop revolution. Two sonic innovators with distinctive sounds that changed brass playing.

J.J.’s style was a revelation when he hit the scene and trombone has never been the same since. He was present at the birth of bebop. On Miles’s “Walkin’” session he ushered in hard bop. He was also a key part of the “third stream” movement, establishing himself as one of jazz’s most sophisticated composers. But after the 60s he was generally a classicist, retaining his refinement but not pushing into new territory.

Miles however led a career of constant reinvention. Each new decade was accompanied by radical musical rebirth, never looking back.

Yet, this divergence in their musical trajectories didn’t seem to effect their strong friendship.

J. J. was born in 1924 in Indianapolis. Miles was born 1926 in Altin, Illinois but raised in East St Louis. It’s about 4 hours from Indianapolis by car.

Both arrived in NYC as young wiz kids. J.J. said in his interview with David Baker:

I first met Miles Davis while he was going to Juilliard. He was a student in Juilliard when we first met. We became very good friends. I don’t recall under what circumstances that happened, but it did happen. Even though Miles was going to Juilliard, he found time to go out and jam and for us to buddy-buddy around with the other musicians who were available to buddy around with at that time. We would get together and compare notes about the changes of some of the more complex – the more advanced harmonies such as tunes like Confirmation. It was a challenge to get together and compare notes about how to approach improvisation on that kind of sophisticated harmonic approach, and it was fun to do. I found Miles to be funny. Miles through the years projected an image of aloofness and you might even say indifference to some social situations, and yet for Miles to be one of your friends you couldn’t have a better or closer friend. He would give you the clothes off [his] back. If you were one of Miles’s friends, you had a true friend in Miles Davis. I feel fortunate in having been in that column of people who we characterize as friends with Miles.

Miles said in his autobiography:

After I started playing with Bird’s band, me and Max Roach got real tight. He, J. J. Johnson, and I used to run the streets all night until we crashed in the early morning hours, either at Max’s pad in Brooklyn or in Bird’s place.

Apart from being “tight”, they appeared on a dozen recordings together, starting auspiciously with Charlie Parker in 1947. J.J. was Miles’s first choice for Birth of the Cool in 1949. He couldn’t do the first session but did some later ones.

J.J. managed to score a rare coup of having Miles as a sideman on his 1957 piece Poem for Brass.

When they weren’t playing together, they played a game of ping pong recording each other’s compositions. Miles recorded J.J.’s Kelo and Enigma in 1953 with J.J. present in his sextet. In 1957 he recorded J.J.’s most famous composition, Lament, as part of Miles Ahead.

J.J. recorded Miles’s Solar (1956) Blue Haze (1957), Tune Up (1958), Neo, Swing Spring and So What (all in 1964). J.J.’s band was also an incubator of sorts - Paul Chambers and Victor Feldman played with J.J. before they played with Miles.

Perhaps most surprising about this bromance is the existence of a “lost sextet” that Miles put together in 1961. After the dissolution of his most famous group from kind of blue, and a wild final European tour with Coltrane, Miles needed something new. He turned once again to his buddy J.J.

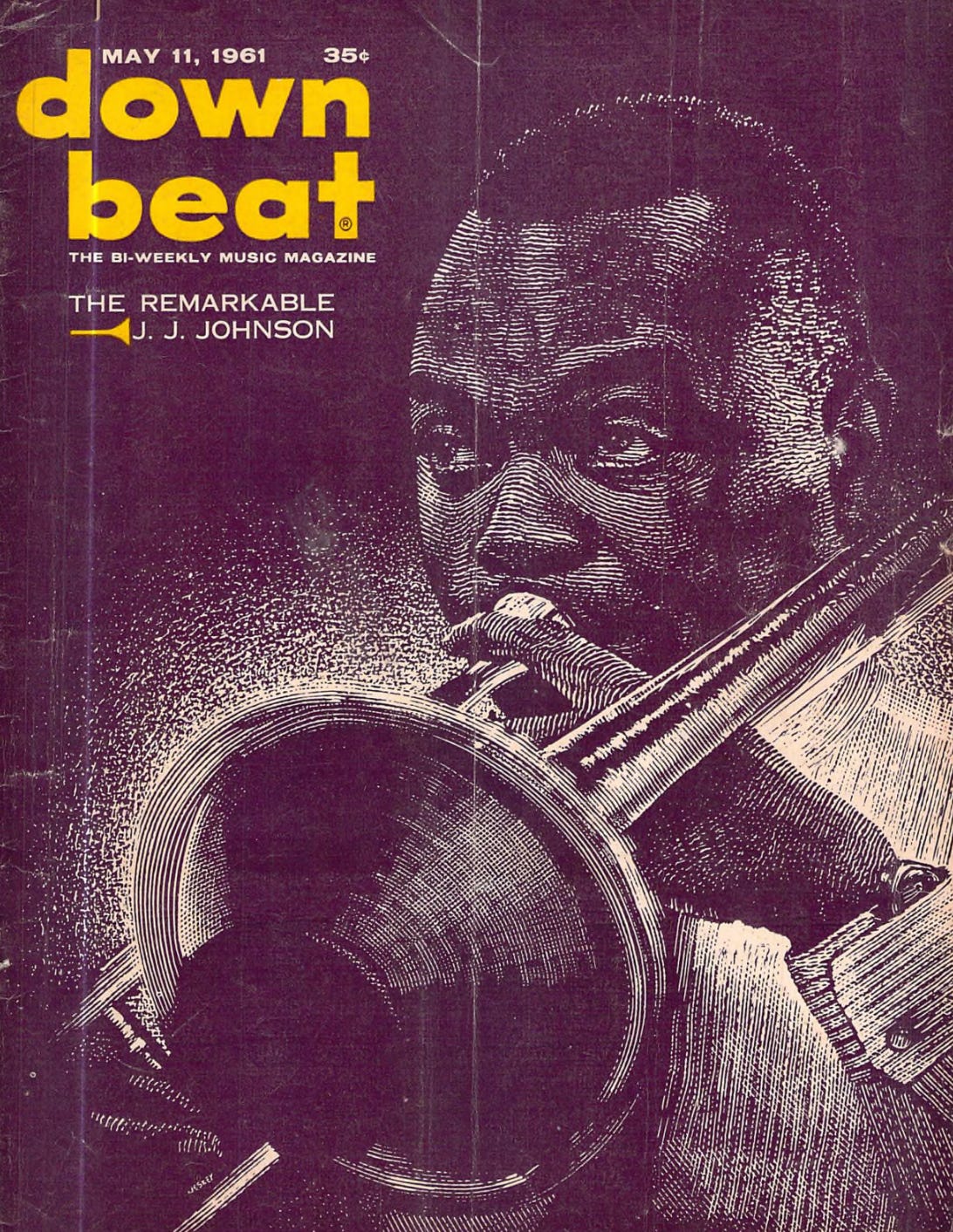

In the final moments of a 1961 downbeat interview J.J. said coyly

Maybe I will get another group now that I’ve had a chance to catch up on a bit of relaxation. On the other hand, perhaps I’ll accept an offer that was made to me by a certain jazz artist who indulges in sports cars, Italian-cut suits, and the stock market.

There is some confusion about this group, who was in it and exactly how long they toured for. But all seem to agree it was the better part of 1961 and 1962, and the group was astoundingly never recorded.

From “Miles”:

In 1962, J.J. Johnson was available, and Sonny Rollins came back and made some gigs, so I got a real good sextet together with Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers, Jimmy Cobb, and myself, and we went out on the road.

…

We finished playing Chicago in December 1962 - myself, Wynton, Paul, J.J. and Jimmy Cobb; Jimmy heath came in for one gig taking the place of Sonny Rollins, who left again to form his own group and to go back and woodshed some more.

But according to an interview J.J., the band had Hank Mobley. David Baker recalls seeing the band in Louisville, and swears it was 1964, which doesn’t really make sense:

Johnson: I was with Miles between a year and a half to two years, I would say, roughly.

DAVID BAKER: [whistles]

Johnson: Very, very roughly. We toured all over. We didn’t record at all.

DAVID BAKER: You didn’t record, not one record.

Johnson: Not one record did I make with Miles during that cycle. I don’t know why. It will never be know why we didn’t record that particular group. It was a wonderful experience. Miles and I just got closer, even more so with that relationship.

While the band was on tour, Miles’s father died. J.J. broke the news to him.

Scholars seem to agree that the band played 1961-1962 and did not have Sonny Rollins. At the end of the group’s touring J.J. participated in the recording session for “Quiet Nights” as a section member.

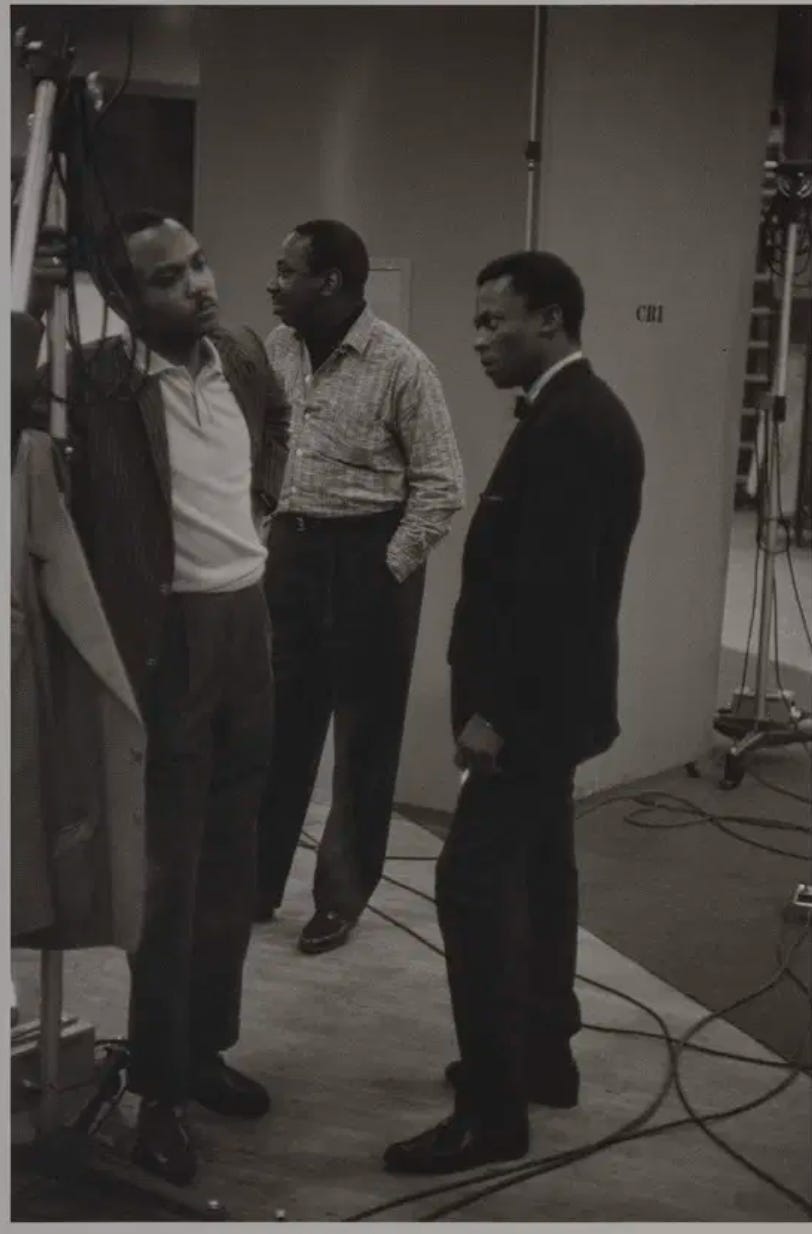

Oddly, although there is no recording of the band, there is a very good collection of photographs of the band in Chicago from Laird Scott.

The existence of this band and the lack of recordings adds to one of the great mysteries of jazz trombone, especially important to me: why, at about this time, in top small groups, it appeared as a solo instrument less and less frequently. Perhaps if Miles had decided to record he would have had another legendary group that spawned legions of imitators and the trombone would be indispensable to modern jazz groups. Perhaps Miles, the legendary taste maker, correctly sensed that the group was not quite succesful, not worthy of recording, and therefore he rightly kept experimenting with personnel until he settled upon his legendary second great quintet.

There is a parallel mystery here: why did jazz trombone not produce a player adept at the most virtuosic 60s jazz, who could keep up with the innovations of the Coltrane Quartet, Miles Quintet, and the younger Blue Note groups. Ethan Iverson likes the term “Interstellar Hard Bop” to describe uptempo, harmonically advanced, swinging jazz of the era, which emerged from the innovations of Miles and Coltrane, and identifies five representative tracks:

Herbie Hancock, “One Finger Snap”

Wayne Shorter, “Witch Hunt”

Joe Henderson, “Inner Urge”

Larry Young and Woody Shaw, “The Moontrane”

McCoy Tyner, “Four by Five”

Who is the trombone player of the era who would have been comfortable on these types of tunes with these groups?

My speculation is that, although JJ possessed the technical skills to do it, he had a different aesthetic (and this also applies to virtuosos Curtis Fuller and Slide Hampton).

I’m still preoccupied with trying to be articulate and clear and to approach jazz improvisation with logic…The preoccupation was to try to make sense and try to put logic into my lines, if they were lines. That was the preoccupation, to make a statement that was clear, articulate and with logic. Not with speed.

Perhaps this emphasis on clarity and being articulate was contrary to the aesthetic of Interstellar Hard Bop, which required a certain angularity and abstraction to be successful. Like J.J., Miles and Coltrane started out with styles rooted in bebop. But as the 60s progressed they changed their vocabulary to something new. J.J.’s evolution was more subtle.

J j was fully onboard Miles’s innovations in modal jazz exemplified by “So What”. J.J. did a big band version of the tune on his album “J.J.!”. His solo is swinging, tuneful and incorporates the sense of modal improvisation that Miles pioneered: upper intervals had the same emphasis as the lower notes of the chord. Not all bop based players were adept at this transition. Listening to Miles’s sidemen Hank Mobley and Sonny Stitt play this tune, one gets the sense that they were still applying the bop based, 2-5-1 vocabulary to the modal framework.

Later J.J. would record Miles’s modal “Neo”. Coltrane’s “Impressions” led to some especially inspired playing from J.J. on a live set from Newport in 1964 with the young band of Harold Mabern, Arthur Harper and Louis Hayes. J.J. demonstrated he had the chops to keep up with the young burners. It still lacks the abstract quality of Interstellar Hard Bop.

The early 60s approach to modal harmony was not the end of the story. Miles did not stay still with the tuneful, harmonically static strategy that he began with Kind of Blue. In his later solos with his 60s quartet on So What, the tension is ratcheted up along with the tempo. He sits on dissonant harmonies for lengthy segments. His vocabulary is increasingly chromatic, blurring the line between chord tones and dissonances. Phrases are often over the beat and there is an underlying aggression. Compared to J.J.’s emphasis on “logic” and “articulate statements”, the logic is intentionally obscured. Solos by Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter magnified those tendencies.

By 1970 Miles’s playing and band leading had entered new ground. While Miles was initially skeptical of free jazz, in his book he had this to say about “on the corner”:

It was actually a combination of some of the concepts of Paul Buckmaster, Sly Stone, James Brown, and Stockhausen, some of the concepts I had absorbed from Ornette’s music, as well as my own. The music was about spacing, about free association of musical ideas to a core kind of rhythm and vamps of the bass line.

Compare with J.J. in this 1970 Downbeat interview:

Several years ago, there appeared on the scene a number of musicians who looked upon themselves as the saviors of jazz. These players went around shooting off about ‘ way out this’ and ‘ avant garde that,’ but in the end they didn’t fool anyone but themselves.

I’ve been a Coltrane man from the very beginning and still am today. Innovation always has been— always will be— a crucial part of jazz. The heart and soul of the music has always been embodied in its innovators

The press and the promotion corps really jumped on the ‘ avant garde’ band- wagon, but they jumped so hard they broke down the entire gig. If that ` way out’ music had been given some time, it might have been able to find itself— it might have meant something. The exaggerated notice precluded this possibility. So jazz has been at a standstill--businesswise. But not in the way that it really counts— creatively.

But he still professed an open mind:

Lately, like everyone else, I’ve been listening to a lot of rock. Some because it is interesting, some simply because I want to know what’s happening. Musically speaking, a lot of the rock being ground out today is not particularly interesting to me. At the same time, some rock groups are really making sense, and I listen to them live and on record.

While Miles was making a heady mix of world music, experimentalism, dissonance, and funk, J.J. was making more commercial records for A&M/CTI with Kai Winding. The oddest of those is “Betwixt and Between” (1968). While Miles’s records combined many influences into a thick stew, J.J. and Kai presented disparate styles as juxtapositions. It’s a bizarre swinging sixties contrast of Prokofiev, Bach chorales and inventions with funk grooves and covers of recent pop hits.

Their tastes had diverged. However, they were not completely at odds. On the back cover of “At Fillmore” (1970), Miles’s old buddy gave a quote.

J.J. Johnson, trombonist, composer, arranger: “I didn’t get to the Bowl concert, but I saw Miles at Shelly’s Manne-Hole that week. I had to go and see if it was true, what the guys on the street were saying. It was. If you want my general opinion, I’ll tell you what I’ve got to say about Miles: I approve! It’s out there, what he’s doing. But I approve. Listen, Miles is doing his natural thing, he’s just putting it into today’s setting, on his own terms. If you put Miles and his new group in the studio and recorded them on separate mikes and then you cut the band track and just played the trumpet track, you know what you’d have? The same old Miles. What’s new is the frame of reference. I’ll tell you something else about that kind of music. Kai (Winding) and I tried a similar thing at A&M recently that hasn’t been released yet. We let fly—and that stuff feels great to play! Miles knows what he’s doing.”

The album he’s talking about is presumably J and K’s “Stonebone” (1970), and the connections to Miles are clear. In addition to featuring Miles veterans Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and George Benson, the group covers Joe Zawinul’s “Recollections” arranged by Bob James. I don’t know how this group got connected with this piece, but it appears they recorded it in Sep 1969. The same piece was recorded by Miles in Feb 1970 and eventually released on Big Fun in 1974.

Comparing the two versions lays plain the differences between J.J.’s and Miles’s approaches. J.J.’s has a moody intro, a swinging interlude with a bouncy Grady Tate, and an extended funk vamp. Miles’s version doesn’t stray from the atmospheric, mysterious intro for 18 minutes. J. J.’s is radio friendly. Miles’s is what you put on when you have friends over to take acid.

Stonebone starts off with “Dontcha Here Me Callin’ To Ya” by the Fifth Dimension, also a favorite group of Miles. J. J. takes a long, swaggering solo (again over “So What” changes). While it’s a gas to hear J.J. let loose in this context, it’s nowhere near Bitches Brew. J j didn’t really play differently in this period. His playing over funk vamps is not that different than his playing over, say, Horace Silver’s Cape Verdean Blues or his own recording of Neo.

Miles solos are longer, more piercing, slashing, he stays in the high register. His harmonic sense was still evolving. The second quintet era still featured many tunes with traditional chord changes, although they were put to use in new ways that broke from functional harmony. But the Bitches brew era featured new harmonic ideas like overlapping triads, related by major thirds.

Miles Lays the Voodoo Down featured Miles playing a (very Stravinskyian) harmony with a major triad over a minor triad, the inverse of the classic “#9” or “Hendrix” chord. These ideas reflected new ways of thinking of jazz harmony that could not be encapsulated by traditional chord changes. Along with his extreme athleticism, his vocabulary was changing. These harmonic innovations were reflected in his style for years to come.

Both men responded to the dark ages of the jazz industry by taking a break. For Miles this was isolation in his upper west side brownstone in 1975-1980. For J.J. it was a move to LA around 1970. He scored Blaxploitation movies and action TV shows and played third trombone in the Carol Burnett band.

Miles’s use of electronics on the trumpet in the 70s is well documented. Lesser known is J J’s fascination with tech.

Downbeat, 1961:

(He explained his aptitude for the mechanical and technical with the comment, “I always liked to tinker around. Now it’s with hi-fi.” Charles Graham, Down Beat’s high fidelity editor, says, “J.J. has even more equipment in his house than I do.”)

After his return to performing, in 1980, he released “Pinnacles” which was largely straight ahead but also featured him using a mouthpiece pickup and a harmonizer over funk beats on a few tunes. Compare to Miles’s 80s comeback band which had a coked-out edge to it. J.J.’s toe dipping into the waters of electrified funk is restrained, classicized, and cool.

Miles vowed never to look back. But J. J. did look back. His later albums were mainstream 80s and 90s swinging jazz. Occasionally you get a glimpse of his third stream predilections. On Quintergy: Live at the Village Vanguard (rec 1988), on the intro to Why Indianopolis - Why Not Indianopolis he does a free form unaccompanied solo that veers into dissonance.

His version of Nefertiti is a glimpse into what he might have done if he had a 60s quintet devoted to exploring the new music. He doesn’t solo, leaving the modernist explorations to Stanley Cowell, Rufus Reid and Victor Lewis.

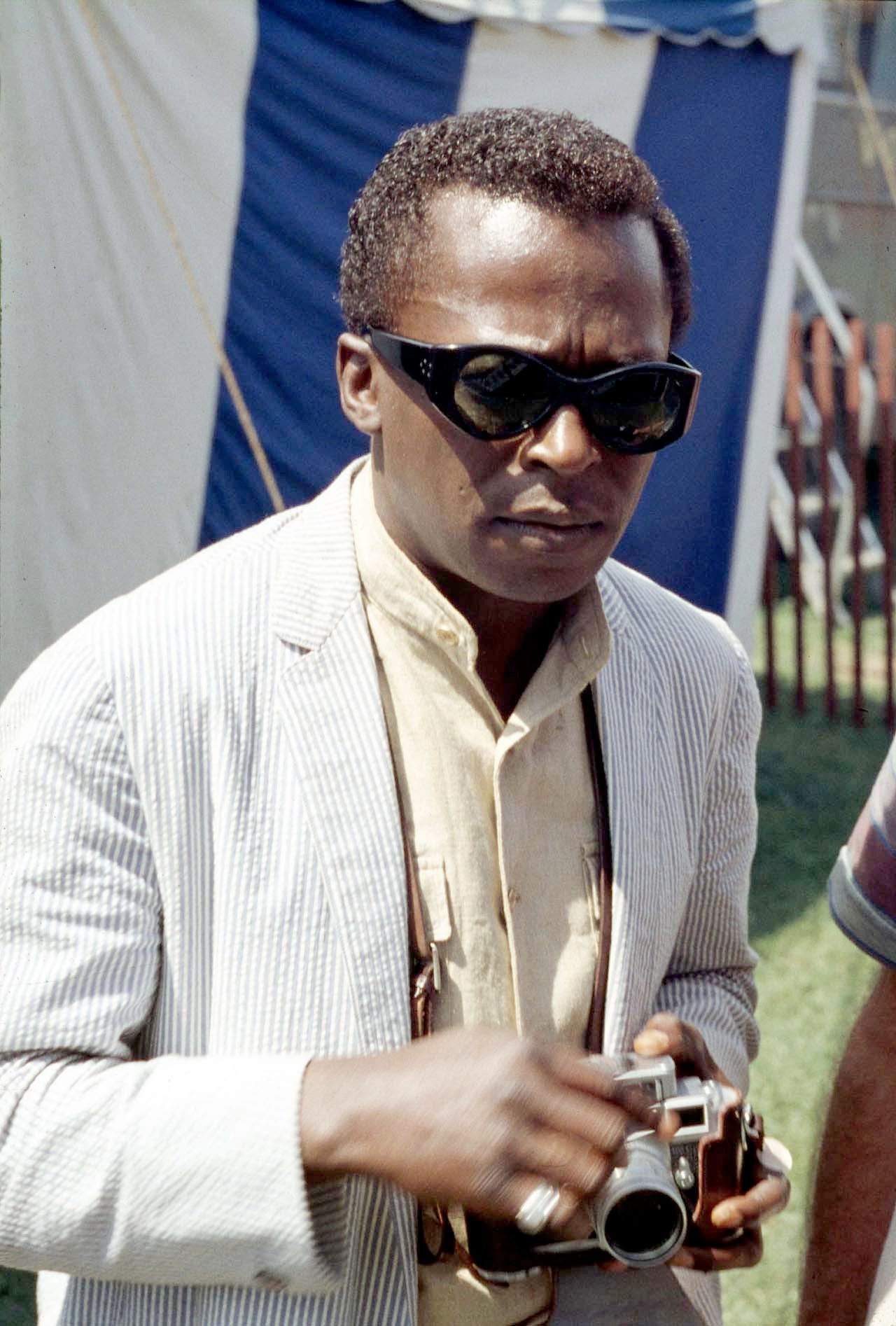

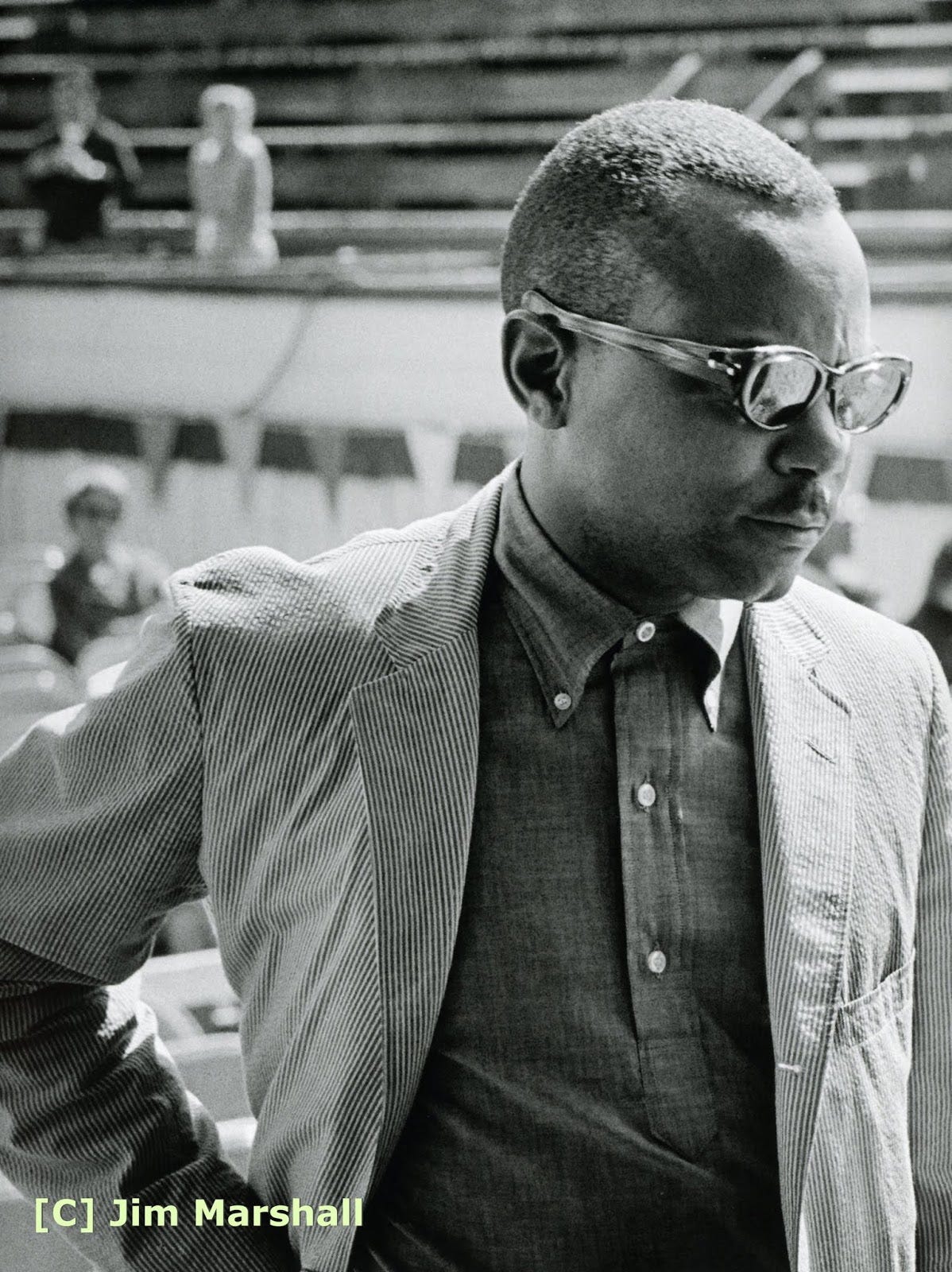

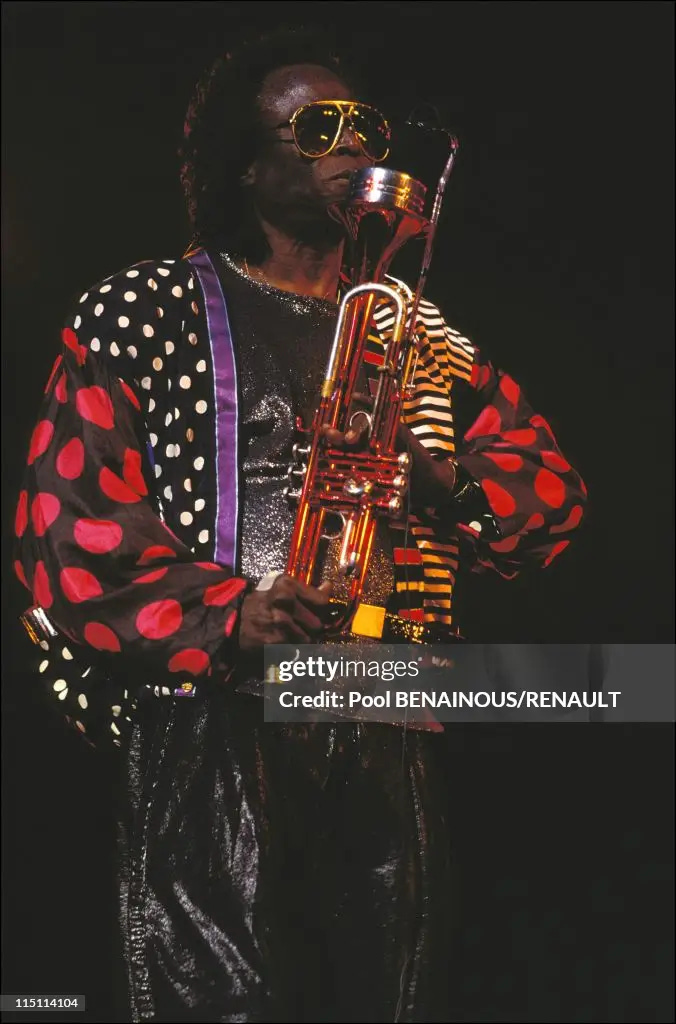

The biting and insightful social media character Derek Guy aka menswear guy has long talked about the importance of jazz musicians and in particular Miles Davis to 20th century fashion. The “ivy” trend ignited when jazz musicians adapted the collegiate wardrobe of ivy leagues. This in turn spread to young English mods (short for modern jazz). Both Miles and J. J. were patrons of the Andover Shop in Massachussets and thus at the vanguard of this new trend.

However it’s illustrative to compare later photos and note the difference in change to their wardrobes. Miles, the clothes horse, adapted in the 70s and 80s an avant garde aesthetic with edgy, experimental costumes that are studied to this day by fashion historians. There are blogs obsessing about the details of Miles’s watches, his sunglasses, or his baggy jeans. J. J. in the 80s and 90s, by contrast, looked more like a college professor than a rock star.

Miles in his final decades was hanging out with Andy Warhol, John Lennon, and Prince, appearing on TV shows and in movies, but he stayed close with his old friends from the bebop days.

Johnson: Yeah, a very dear, dear friend. It’s interesting that he was the most concerned person when another person was in bad health. I’ll never forget. I happened to be with him. He was living in Malibu in California. We were both living in California at the time, and I was visiting Miles just buddy-buddy style on a given afternoon. Someone called Miles to tell him about Clark Terry being in poor health. Miles grabbed the telephone and called somebody and said, “Get me Clark Terry.” He had trouble getting through to Clark Terry. He told this person, “Find out what the situation is with Clark Terry and whatever Clark Terry needs, you see that he gets it. And if there’s any problem, you call me about it.” He was very concerned about Clark Terry’s health and about Clark Terry’s welfare, and he issued orders and demands. “You check this out and find out what’s the story on Clark Terry, and you make sure he’s taken care of. If he needs any money, you let me know.”

DAVID BAKER: That is so [beautiful], and see, that’s a picture that you never see.

Johnson: You’ll never hear that about Miles. All you’ll hear about Miles is him turning his back on the audience and pointing his horn towards the floor. But he was one of the most generous human beings alive to people he loved, and he was a dear, dear friend.

Absolutely brilliant deep dive into this musical friendship. The detail about that unrecorded 1961-62 sextet is wild becuase it couldve shifted jazz history entirely. Had a similar experince digging through old recordings and discovering these untold stories. The point about JJ's emphasis on "logic" versus the abstract approach needed for that mid-60s sound realy explains alot about trombone's trajectory.

Sending thanks from Australia - awesome read!