Ornament, Architecture, and Modern Jazz

How my house obsession dovetails with my jazz obsession

In my essay “Envelope Revolution”, I talked about the mid 20th century changes in brass playing, away from ornamentation and vocal-like expressiveness, towards clarity of articulation, minimal vibrato, and steady breath control. This aesthetic didn’t arise in a vacuum, but ran parallel to a greater movement in the art and design world toward clean lines and lack of ornament. To explain the context of the sparse, clean attacks of bop/hard bop players like Dizzy Gillespie, J.J. Johnson, and Curtis Fuller, it’s helpful to take a step back and look at how the changing aesthetics of music were mirrored in another artistic discipline, architecture.

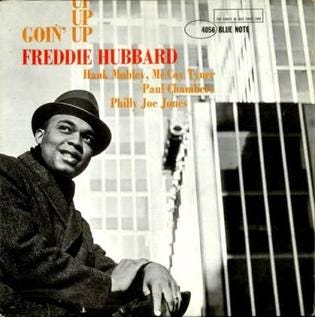

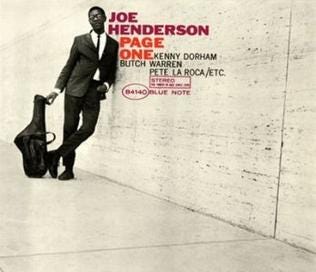

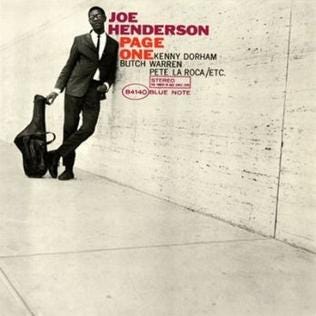

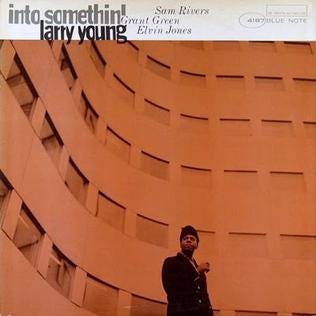

In the marketing of the mid century era, jazz musicians were presented as icons of modernity. Record covers of the 50s and 60s featured abstract artwork, modern architecture, or sometimes the musicians themselves posed in front of buildings. Most of these I assume were the editorial decisions of people like the photographer/label owner Francis Wolff. I don’t know if Joe Henderson specifically asked to be photographed in front of the new concert hall at Lincoln Center.

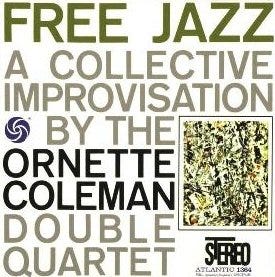

In some cases, like with Ornette and Jackson Pollock, there was a stronger connection between the musician and the artist depicted on the cover - Ornette dug Pollock.

Joe Henderson

Page One (1965)

Larry Young

Into Something (1965)

Freddie Hubbard

Goin’ Up (1961)

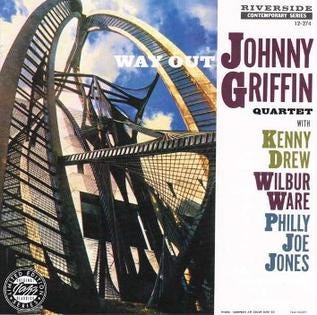

Johnny Griffin

Way Out (1958)

Ornette Coleman

Free Jazz (1961)

Keep in mind the boldness of these pairings - these buildings and works of art were just a few years old, or in some cases brand new.

Just as jazz brass players moved away from the “sliding, slurring, lip trilling or 'gut bucket'” style, as J.J. Johnson put it, to arrive at this modern style, architects had undergone a similar shedding of ornament towards clean and minimal lines.

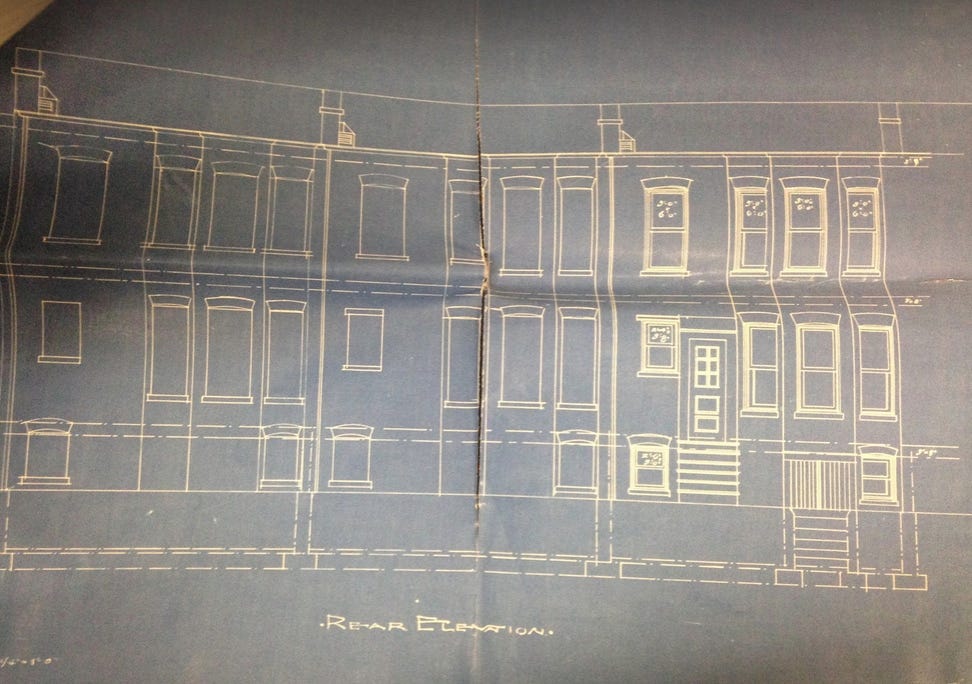

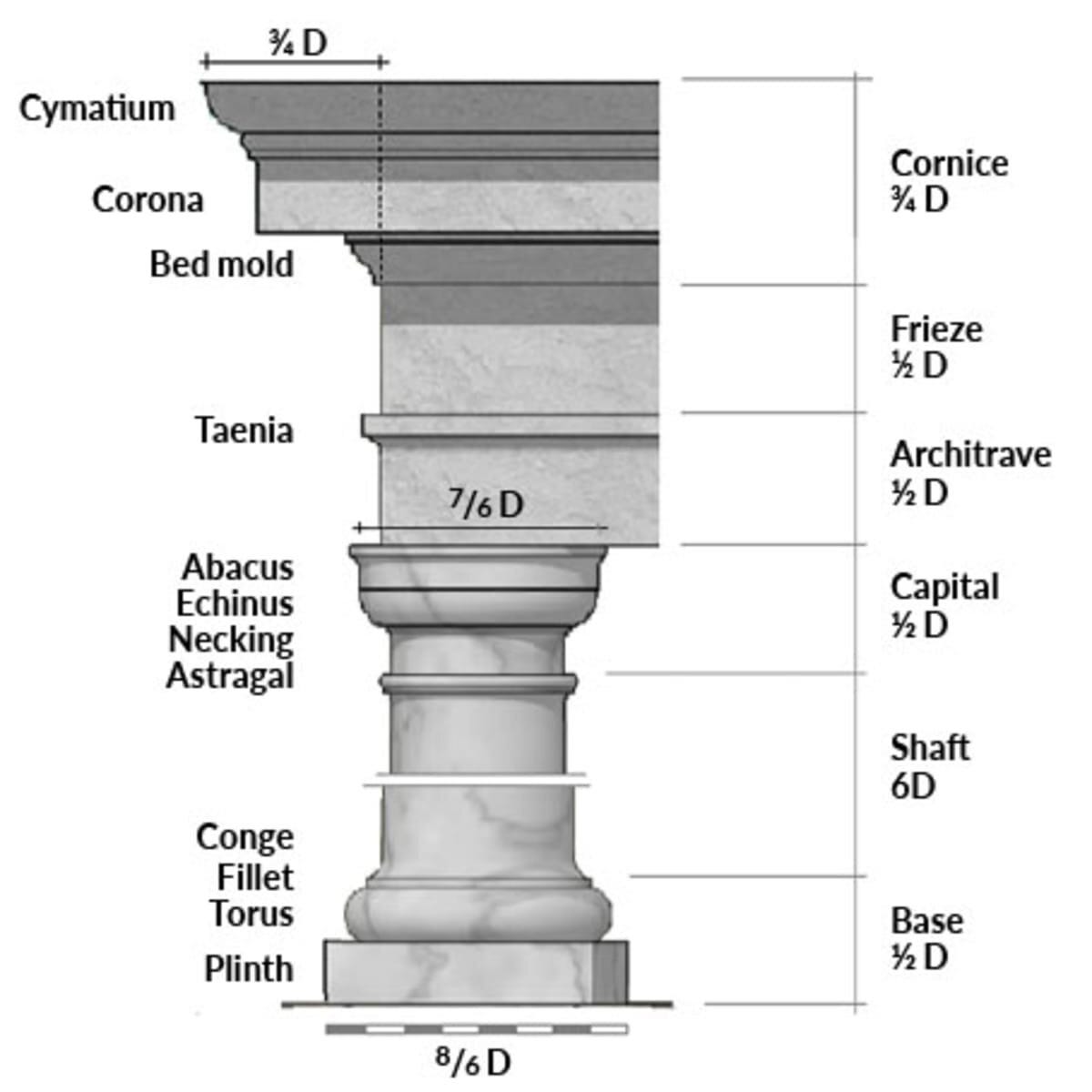

About a decade ago I became fascinated by architecture and Brooklyn, an obsession ignited by the process of researching and restoring the 1909 Flatbush brick rowhouse that I am fortunate enough to live in. When fixing a leaky front balcony, I sadly realized that I couldn’t afford to restore the original wooden gutter and would have to replace it with an ahistoric metal gutter with a different molding profile. I began to wonder what exactly this original profile was. Old house stuff, molding, cornices, window casings, door frames, fireplace surrounds, that which the brownstone fetishists and real estate brokers refer to as “original details”: What was it exactly? I had a vague idea that decorative elements of these century old houses were crafted by hand by genius artisans according to some arcane lost art that involved the study of golden ratios in the finest schools in Paris. I began to look at old digitized archives of the Brooklyn Eagle, the Real Estate record, blueprints, books about brownstones, books about house styles, and as my obsession grew deeper my questions multiplied

.Around the same time my house was built, in 1910, at the Akademischer Verband für Literatur und Musik in Vienna avant garde architect Adolf Loos gave a lecture titled “Ornament and Crime”, in which he declared war on the decorative architecture of centuries past, with typical Viennese intellectual bombast:

I will not subscribe to the argument that ornament increases the pleasure of the life of a cultivated person, or the argument which covers itself with the words: ‘But if the ornament is beautiful! …’ To me, and to all the cultivated people, ornament does not increase the pleasures of life. If I want to eat a piece of gingerbread I will choose one that is completely plain and not a piece which represents a baby in arms of a horserider, a piece which is covered over and over with decoration. The man of the fifteenth century would not understand me. But modern people will. The supporter of ornament believes that the urge for simplicity is equivalent to self-denial. No, dear professor from the College of Applied Arts, I am not denying myself! To me, it tastes better this way.

Adolf Loos was declaring war on the “original details” that fill the nooks and crannies of Brooklyn brownstones. But note how similar his decisions are to the midcentury wind players, jettisoning the swing era expressive attacks for a new clarity.

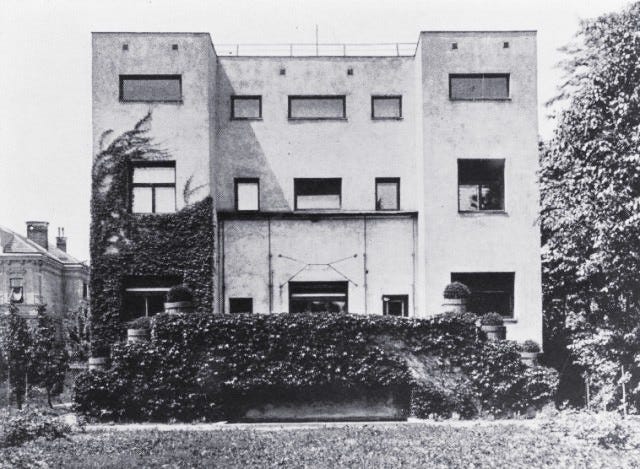

Here is Loos’s state of the art 1910 house compared to my cookie cutter 2 family 1909 house in Flatbush.

My house is florid, ornamented, with a decorative cornice connecting the roof to the facade, and fanciful flowered stained glass transoms, windows surrounded by classical molding and stylized lintels, the large stones over the windows and front door. It’s loosely built in a style called “Renaissance Revival”, referencing the Italian Renaissance and buildings from 5 centuries ago. Aimed at providing a flavor of upper class Europe for working class mostly immigrant buyers striving to make it in the New World, it is a house of the past.

Loos’s house is blocky, austere, geometric, with windows surrounded by nothing. It is the house of the future.

The decorative elements inside and outside my old fashioned house were ordered from catalogues, produced at saw mills, made en masse with automated machinery that was not yet electric but probably water powered and not that differently made than anything wood from a factory today. The molding looked the way it did because the small time Swedish American architect copied the profiles from Italian Renaissance building details that were themselves copied from Greek and Roman architecture 1000s of years prior. A mechanically reproduced copy of a copy. I still think it looks cool. I just don’t think it’s special. (I riffed on the history of Brooklyn architecture’s stylistic revivals of revivals in my record “Ye Olde”.)

At the same time my house was built, this type of abundance of ornament was everywhere. Visual art, interior decor, fashion, literature. It was a busy, florid period. Music was no exception. Orchestras were huge. Symphonies were long. Harmony was dense.

Loos’s house was pointing to a future and aesthetic that yearned to be as far away from the old style as possible. Swiss architect Le Corbusier cited Loos’s polemic in his own writings. In the 20s he was to design his own starkly modern minimalist houses, devoid of ornament, along with highrise designs known as “Towers in the Park” that proved to be widely influential. NYC is blanketed with “Towers in the Park” Corbusian style housing, much of it subsidized for low-income residents and championed by Robert Moses. NYC Jazz musicians were surrounded by, and sometimes lived in, these buildings. Some of them were displaced by the construction of these buildings.

By the mid 20th century, a Loos-ian/Corbusian aesthetic was in full swing. Modern architecture and design was geometric, streamlined, devoid of extraneous external bric a brac. World’s fairs brought the latest scientific ideas and a sense of optimism to the public in Chicago and NYC, including examples of modern architecture and design. The 1958 Brussels World’s Fair featured the Philips Pavilion designed by the office of Le Corbusier under the management of composer/architect Iannis Xenakis, who also wrote sliding, microtonal works based on the mathematics inherent in the building. Science, music, art, and architecture came together as one.

One musician who was very much a fan of modern architecture was David Brubeck, who commissioned both a 1954 house in Oakland and a 1961 house in Connecticut, both by Beverley David Thorne.

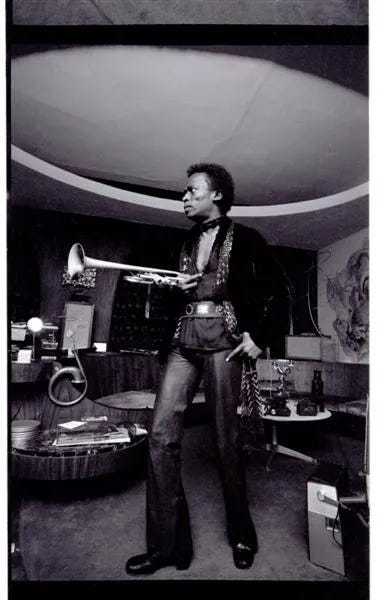

Always a trailblazer, Miles Davis had a history of living in cutting edge modern architecture. In a very Miles-ian metaphor, his Upper West Side brownstone was gutted, the original classical details removed, and renovated in an avant-garde late 60s style that was profiled in the New York Times. He declared: “I don't like corners. I don't like furniture. “ Guests sat on the floor. “I got tired of living in a George Washington kind of house.” No colonial revival for Miles.

The decor was psychedlic-era rather than mid-century. But the connections between artist and envorinment were clear.

This is great, especially love the point that a lot of the art/architecture ending up on those covers was new at the time, not sure how much modern architecture makes it onto covers these days! Also the loos lecture is interesting, I totally understand the jump from retro ornamentation to sleek modernity, but I worry that in art, we did it too hard, and forgot that there was a lot of style in ornamentation, some of that style (or emphasis on style) I worry has been lost in the postmodern art scene of today.

Very interesting essay. I lived in several Brooklyn brownstones pre-gentrification.The analogies you make between music and architecture remind me of the saying "Architecture is frozen music". I've heard this attributed to a few different people so I'm not sure of the exact origin. In the early seventies I lived in a building in Little Italy that was owned and occupied by the artist Louise Nevelson. I recall asking her once how her latest piece was coming along to which she replied " I can't find the melody". Your comments about the spareness of later architecture compared to the ornateness of earlier examples reminded me of the way Basie's All American Rhythm section streamlined the rhythmic foundation of jazz and how Lester Young's pared-down style contrasted with that of Coleman Hawkins and other "big toned" tenor men. I also recall remarks made by two players who had a huge influence on me and whom I played with in the same group for a couple of years. Lee Konitz always talked about sticking to the point (as did Monk)and wanting to "trim the fat" from his playing and Jimmy Knepper used to talk about trying to eliminate " filler material" from his playing. Thanks for introducing such an interesting topic. Kepp up the good work.KB