This post is part of a series largely geared towards trombone players. I’m also going to touch on a lot of tangentially related musical goodies.

If you are trombone-articulation curious, read on. Otherwise, sit tight, I’ll have plenty of non-trombone specific content in the weeks to come. No apologies for going so deep into a niche topic. My whole career could be described as going deep into a niche topic.

STEP 1: Strengthen Your Single Tongue

Although this series is about double tonguing, a considerable technical hurdle, most of my practice is not focused on double tonguing. My daily routine revolves around single tonguing. Regardless as to whether you ended up developing a strong double tongue you need to have a strong single tongue.

My practice starts with slow single tongued major scales in the low to middle register. This is my warm up. This method was taught to me by Dave Taylor. He does this exercise, along with some minor variations, for up to 2 hours daily. His students have adapted this to their own practice. When he taught it to me 25 years ago I experimented with doing the whole lengthy routine but over the years I have shortened it to be only the scales F, F#, and G. I usually do the warm up exercise with a metronome at a very slow tempo, eighth note equals 60. It takes me about 20 minutes.

The focus of the routine is on warming up the diaphragm, lungs, and tongue, while keeping the embouchure relaxed. I don’t do lip slurs or long tones to warm up.

For G, in the bottom of the bass clef, and below, the tip of the tongue touches the upper lip and top teeth. This technique is also used for other registers when a very hard tongue is required. For low Ab and above the tip of the tongue touches the top teeth. For legato tonguing the first note of a phrase is a “ta” and subsequent notes are “da” with tip of the tongue on the roof of the mouth (the alveolar ridge).

As you inhale, contract the diaphragm and expand the lungs. Play everything with as much air in the tank as possible. These breathing techniques are the same as you would learn in any yoga class.

Over the years I have done a variation which incorporates fast repetitions of single tongue but most of the time now my method for increasing single tongue speed is improvising.

I can single tongue 8th notes up to q=260, although I usually will have already switched to double tongue at that tempo.

The threshold at which most players switch from single to a paired articulation is worth thinking about for a minute. Many teachers stress the importance of increasing single tongue speed to facilitate these tempos. However I took the opposite approach - I became more comfortable double tonguing at slower speeds, eliminating the necessity to quickly single tongue.

In a video about tonguing, Elliot Mason explains why he prefers single tonguing for all but the fastest tempos:

Single tonguing, which I kind of use, I would say, 90% of the time. Why? Because I like the shape of the note. I feel like it's it's like my largest shape of the note, and so, full sound at all registers, and I can also kind of accent whichever note I feel. I can also jump around, where with other tonguing, sometimes it's hard to do that with the second syllable or stuff like that. So this is why I try and use single tonguing for the majority of the time.

I think he’s right that most players feel more comfortable with single. However, the second, kah, syllable of double tonguing can produce a full tone and it is potentially as rhythmically flexible as single. Single tongue is not inherently easier to accent than paired articulations. Many players feel comfortable with distributing accents using single tongue because they have practiced it for years. The same level of comfort can be achieved through practice of paired articulations. Repetitive single tonguing is not natural to jazz musicians. Think of scat singers: usually they use a mix of syllables, often paired like “doo-ba”. “Ba” cannot be used as an articulation on a brass instrument because it uses the lips. But the pairing is illustrative of what works well with jazz.

Very slow legato double tongue is quite useful - the “ka” syllable can be very delicate. It’s great for many kinds of legato passages.

In Javier Nero’s dissertation on jazz and double tonguing, during an interview with Ronald Westray, Javier mentions an anecdote that is illuminating about the issues jazz trombonists face with the tempo threshold.

I heard a story that Slide Hampton used to like to call tempos on Curtis Fuller to put him on that threshold so he couldn't play his stuff.

The following examples are meant to illustrate the challenges posed by the threshold tempos. They are not works of art, nor are they perfect. If you’ve been reading my substack you’ll know my opinion of perfection!

In this example, around 200, I’m using a combination of single tonguing and lip slurs.

Here at 234, still using only single tonguing/lip slurs, my options are more limited. I can perhaps do 4 or 5 single tongued notes in a row before the tongue gets fatigued and starts to drag. In addition, the restriction of single tongue means the 8ths must be more even. However this type of practice is still worthwhile - with the absence of longer 8th note lines, one is forced to build their fast note strategy.

Here’s ~200 but with double tonguing. In a concert situation I might do a mix of single and double for longer 8th note lines but this is still a good exercise.

Here is 234 with double tonguing. Note that strings of 8th notes can now be very swingy/uneven, unlike single tongue. Double tongue works well even for a more conventional jazz style.

STEP 2: Say Ka

Myth: a Ka syllable is not worth practicing on its own, only when paired with double tongue.

Throughout this series, I will stress the importance of being able to speak or sing the figures before practicing them on the instrument. When I first started out trying to double tongue I was a mush mouthed teenager. I could not say “ta-ka-ta-ka-ta”. It would make me nauseous. I had to get used to the sensation of the middle of the tongue repeatedly hitting the roof of the mouth. This may be related to the braces I got when I was 14 - my mouth was in pain for two years and doing any kind of crisp diction meant more discomfort.

So I practiced first saying slow “Ka”s, then playing them.

STEP 3: Play Ka

Not a ton, not as much as single tonguing, just enough to get used to that sensation and to build the strength of the tongue. A little every day. Now my “ka” is pretty strong. The goal is to build strength enough so that, while playing, the syllable can sound the same as “ta”.

Isolated kas aren’t going to win a beauty contest. Think of it like eating spinach. Eat your vegetables. Mind your ps and kas.

STEP 4: Say Ta-ka-ta-ka-ta

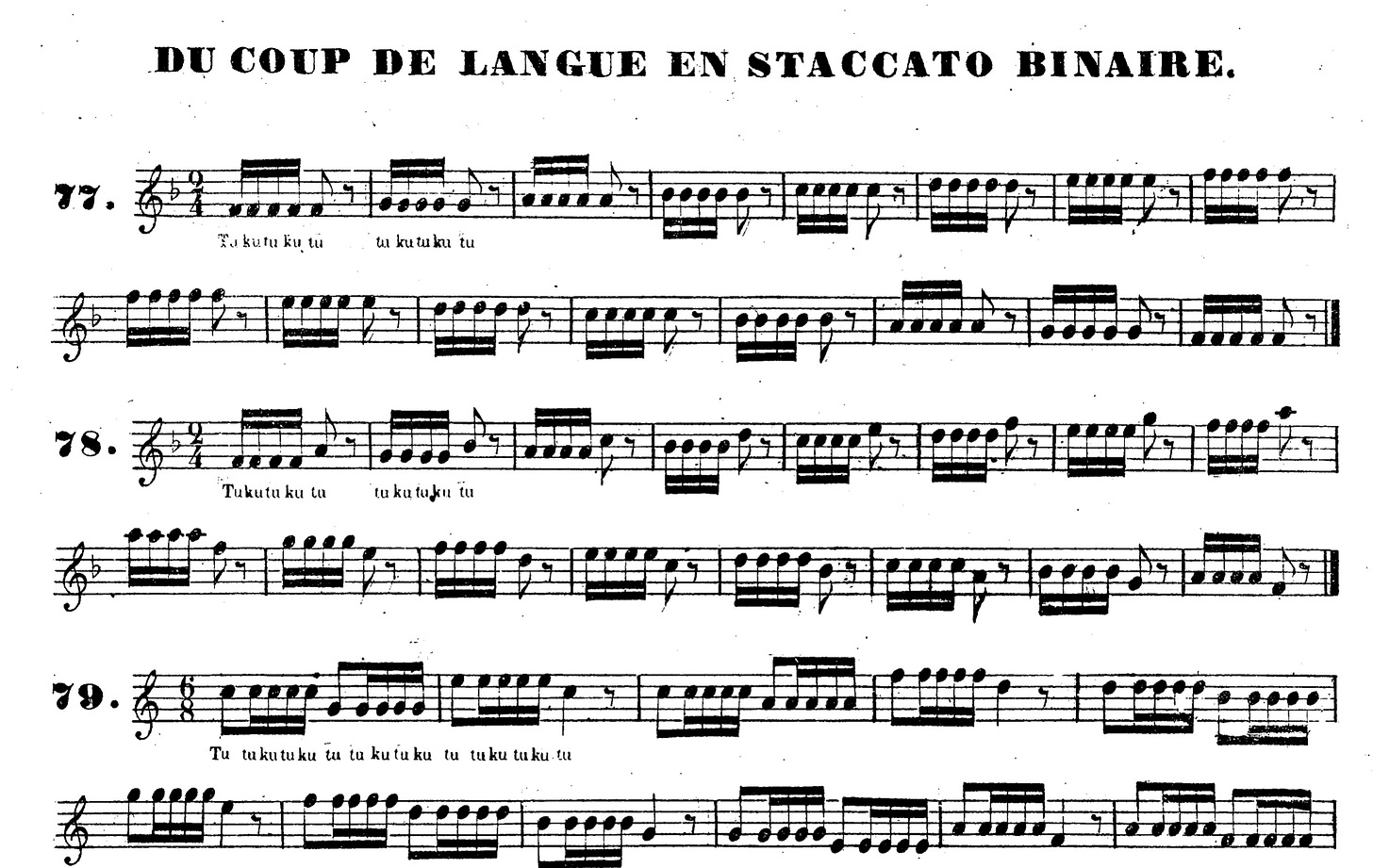

This set of 5 syllables has two “ta-ka” pairs and a final “ta”. Not too many to overwhelm the beginner but more than a single pair, to get some momentum. This is the same way that Arban’s double tonguing exercises start.

Although it’s focused upon a somewhat obsolete style of brass playing, Arban’s is still useful for learning double tonguing. Based upon the Eb major scale, the first double tonguing exercises are restricted to a register that is perfect for beginners. Lower and higher registers have unique challenges which can be addressed by more advanced double tonguers. To start out it helps to have a relatively neutral oral cavity and relaxed embouchure.

The progression from repetitions on the same pitch, to 4 notes on the same pitch followed by 1 new note, to pairs of single notes, to individual notes, is a logical way to gradually train the tongue and slide to coordinate.

Arban’s is organized with triple tonguing before double tonguing. My theory about this is that triple tonguing has a smaller ka to ta ratio than double, so it is a way of gradually introducing ka into one’s comfort zone. A triple tongued set of three notes is 33% ka and 66% ta. A beginner practicing 15 minutes of triple would then feel less fatigued than doing the same amount of double.

The entire Arban’s series of exercises is excessive and not really relevant to modern playing. I haven’t done them all. There are certain ones that are helpful. I would recommend working on the first triple tongue exercise and the first double tongue exercise and doing them at the same time.

Myth: Double tonguing can’t be practiced slowly

I’m not sure how this myth arose. Perhaps it is the difficulty that beginners have with the “ka” syllable. It doesn’t sound great, and doing it slowly exposes these sad sounding attacks.

STEP 5: Play Arban’s #77

I do #77 very slowly, about quarter=45. I try to do it cleanly. I like it, it’s sort of zen. There is no coordination of either slide or embouchure required yet.

#77 very slow tempo

#77 medium tempo

The technical jump from #77 to #78 is considerable. Dwell upon #77. You may have to spend quite a bit of time on it before moving on. I mean like, every day for 3 months. A lot of time! Focus on tempos in the range of eighth note=180-260 and avoid very fast tempos for now.

STEP 6: Triple Tongue Exercise #1

Note that this one has 7 notes in a row while the double tongue exercise has only 5, which is why I would opt to do double first. I use “Tu-ku-tu” rather than the original Arban’s “Tu-tu-ku”. I don’t think it matters much. Perhaps as a jazz musician I like the former because I wanted to have a stronger final triplet. Paradoxically the latter puts a ka on the final triplet, which aligns with double tongued eighths, and having a strong flexible swung ka is the entire focus of this series of essays. Regardless you are going to work towards strength and evenness for all three triplets.

STEP 7: Arban’s 78

#78 adds a complication: the last note changes. So now you have to coordinate slide and tongue. The slide moves a split second ahead of the tongue. Maybe even more than a split second. This little dance of the slide preceding the tongue is counterintuitive but essential. You need to consciously move your hand before your tongue so the slide arrives at the new position just as you tongue is ready to start the next note.

I use a relatively relaxed slide motion. In videos of J.J. Johnson, his slide arm is very relaxed. Sometimes he lets go of the slide cross brace entirely and lets the slide glide between his fingers and his thumb. Some players, especially those trained in classical trombone, use a very fast slide and a very firm grip on the brace in order to minimize the time between notes to facilitate legato. Too rigid for me.

STEP 8: Arban’s 79-86

More of the same. Once you have the hang of 78 you can transfer the technique to change notes to pairs of notes. You are training your tongue to do longer and longer streams of double tongued notes.

STEP 9: Arban’s #87

This is a big one, 5 different notes in a row. Try and make your slide movements fluid. The first and last positions of the slide, for the first and last notes, are the most important. Use alternate positions. When you are going at full speed, the middle notes of each group of 5 are more important to tongue and to buzz and less important to have the slide in exactly the right place.

Here’s #87 at slow, medium and fast tempos

The slow one is marcato but not accented. I would describe the faster ones as quasi-legato.

Congratulations, you are double tonguing streams of different notes. Now it’s time to apply this to jazz and improvisation.

next up: teaching Jean-Baptiste Arban, Professor au Conservatoire Imperial de Musique, to swing

I heard a story that Steve Kellner (former principal euph in the marine band) got frustrated with how bad his K tongue sounded, so he played everyone using only the K tongue for an entire summer.

I read a long time ago about flute players using a "nga" syllable in place of the k tongue. Obviously it's the same place of articulation, but have you ever experimented with this on brass?

Sometimes I work on ka-ta-ka-ta instead of ta-ka-ta-ka. Occasionally I do it in performance. It even seems to affect the content of my ideas somehow.

These are great ideas, I'm going to pull Arban out again.